Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, December 2017

Fratelli d’Italia,

L’Italia s’è desta,

Dell’elmo di Scipio

S’è cinta la testa.

Dov’è la vittoria

Etc.

Incipit dell’ Inno di Mameli (1847)

(Brothers of Italy,

Italy has awakened,

Of Scipio's wind

It is the head.

Where victory is

Etc.

Incipit [beginning] of Hymn, by Mameli (1847)

In one of our essays (1), we have highlighted the double meaning of the expression "to be like the Fool in tarot cards", that is to say, "to be of no value", albeit a card considered of great importance in the game. In fact, the Fool - remembering that the tarot was designed as a pack of playing cards - had no power to capture the other Triumphs (Major Arcana), as Girolamo Zorli, a major historian of card games, points out in his part of our article (2). On the other hand, the expression could point out that the Fool, even though he had no power to capture, could at the same time not be captured by the other cards. It was, in short, a key element. In that sense, widening the concept, 'to be like the Fool of the tarot' could mean being someone you could not do without.

The expression, however, was typically used in common talk with the meaning of “no value” or “something extraneous” that had nothing to do with certain situations or people.

Carducci played tarot, given that it was the most loved and popular card game of the nineteenth century, and he was in good company since we know that Manzoni, Leopardi, Foscolo and many other great names in Italian literature of the time were.in love with the tarot

Since Carducci in his work refers, about Italy, to the expression “essere in Europa quello che è il matto nel giuoco de’ tarocchi” ("being in Europe what the Fool is in the game of tarot"), we find it of interest to undertake a review, considering the fact that the passage was written at a time of Italian political and social history that can be compared to the present situation.

His collection of poems Giambi ed Epodi [Iambs and Epodes], published in 1882, shows itself as a controversial work, as is already evident from the prologue. He intends to condemn the evils of his time, “the bad era”, in the name of betrayed youthful dreams and Freedom yet to be fully attained.

Ululerò le lugubre memorie

Che mi fasciano l’alma di dolore.

Ululerò gl’insonni accidiosi

Tedi che fuman da la guasta età,

Invidïando il rorido fulgore

De’ miei giovani sogni e i desii splendidi

De le infrante catene e gli animosi

Vostri richiami, o Gloria, o Libertà.

Tutto che questo mondo falso adora

Co ’l verso audace lo schiaffeggerò:

Ei mi tese le frodi in su l’aurora,

A mezzogiorno io le calpesterò.

Che se i delúbri crollano e i tempietti

Ove l’ideal vostro, o vulghi, sta,

Che importa a me? Non fo madrigaletti

Che voi mitriate d’immortalità.

Oh, pria ch’io giaccia, altri e più forti fulgidi

Colpi da l’arco liberar vogl’io,

E su le penne de gli ardenti strali

Mandare io voglio il vampeggiante cor.

Chi sa che su dal cielo la Musa o Dio

Non l’accolga sanando e sovra il torbido

Padule de l’oblio non gli dia l’ali

Da rivolare a gli sperati amor?

(I will wail the gloomy memories

That fill my soul with sorrow.

I will wail the sleepless, turbid

Boredoms which smoke from the bad age,

Invoking the lustrous glory

Of my young dreams and splendid desires

Of the broken chains and the braveries,

Your calls, O Glory, O Freedom.

Everything thatthis false world worships

With adverse audacity I will slaughter:

In the morning it pulled tricks on me,

At midday I tromp on them.

If the shrines and temples collapse

Wherever your ideal, O peoples, is,

What does it matter to me? I do not make poor (little) madrigals

To crown you with immortality.

O, before I lie down (die), other and stronger shining

Shots from the bow I want to release,

And on the flights of the fiery arcs

I want to send my blazing heart.

Who knows if above from the sky, the Muse or God

Does not welcome healing, and over the turbid

Bog of oblivion does not give it wings

Toreturnto the hoped-for love?) (3)

In his work Carducci, in addition to extolling the great ideals of freedom, justice and despising the compromises of a united Italy, makes himself the palace paladin towards the Papacy and its ally, France, who have betrayed the values of Freedom gained through the Revolution.

About the Papacy:

Che m’importa di preti e di tiranni?

Ei son piú vecchi de’ lor vecchi dèi.

Io maledissi al papa or son dieci anni,

Oggi co ’l papa mi concilierei.

Povero vecchio, chi sa non l’assaglia

Una deserta volontà d’amare!

Forse ei ripensa la sua Sinigaglia

Sì bella a specchio de l’adriaco mare.

Aprite il Vaticano. Io piglio a braccio

Quel di se stesso antico prigionier.

Vieni: a la libertà brindisi io faccio:

Cittadino Mastai (1), bevi un bicchier!

(What do I care about priests and tyrants?

They are older than their old gods.

I cursed the pope for ten years,

Today, with the pope, I will conciliate.

Poor old man, who knows not the attack

[Of] a desperate will to love!

Perhaps he thinks about his Senigallia

So beautiful in the mirror of the Adriatic Sea.

Open the Vatican. I grab by the arm

That old prisoner himself.

Come: to freedom I make a toast:

Citizen Master (1), drink a glass!) (4)

(1) Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti (Pius IX), who was born in the city of Senigallia.

Regarding France:

Vide il mondo passar le tue legioni,

O repubblica altera.

E spezzare a sé innanzi altari e troni,

Come fior la bufera:

Perché, su via di sangue e di tenèbre

Smarriti i figli tuoi

E mutata ad un upupa funèbre

L’aquila de gli eroi,

Là, ne’ colli sabini, esercitati

Dal piè de l’immortale

Storia, tu distendessi i neri agguati,

Masnadiera papale.

E, lui servendo che mentisce Iddio,

Francia, a le madri annose

Tu spegnessi i figliuoli et il desio

Dì lor vita a le spose,

E noi per te di pianto e di rossore

Macchiassimo la guancia,

Noi cresciuti al tuo libero splendore.

Noi che t’amammo, o Francia?

(The world saw your legions pass,

O republic altered,

Breaking down before them altars and thrones,

Just as the storm destroys the flowers.

Because, on the way of blood and darkness

You lost your children.

The Eagle of Heroes has changed

To a funereal hoopoe.

There, in the Sabine Hills [of Rome], filled

with the footsteps of immortal history,

You [France] made dark ambushes

As brigands for the Pope.

And, serving him [the Pope] who lies to God [by acting contrary to divine teachings],

You, France, from old mothers

Took away their sons, and from

Their wives the desire to live.

And that because of you with tears and redness [blood]

We stain our cheeks, [does it not matter to you, France]

We, who grew up [believing] in the splendor of your [ideal of] freedom

We who loved you?) (5).

At this point, to enter the heart of our argument, we need to highlight Carducci's position and thought on Italy of the time. The poet wrote the Giambi ed Epodi between 1867 and 1872, the period in which Jacobin ideas were welcomed by the poet, tending to support the nascent republican governments and Italian monarchical power that he felt to be the guarantor of popular liberties. Carducci was convinced that Italy would be able to unify without the help and intervention of foreign powers: the lords and citizens, the army and the people, the monarchy and the democratic factions would have united under such an aspiration. Carducci was ashamed, as we have seen, by the French presence, the bad government in the South, the arrest of Garibaldi in Aspromonte and the defeats of Custoza and Lissa. All this had helped him to condemn the politics of the moderates.

Carducci writes:

“E in quell’anno [1866] l’Italia ebbe inoculato il disonore: cioè la diffidenza e il disprezzo fremente di se stessa, il discredito e il disprezzo sogghignante delle altre nazioni. Sono acerbe parole quelle che io scrivo, lo so. Ma anche so che per un popolo che ha nome dall’Italia non è vita l’esser materialmente raccolto e su’ l rifarsi economicamente, e non avere né un’idea, né un valore politico, non rappresentare nulla, non contar nulla, essere in Europa quello che è il matto nel giuoco de’ tarocchi: peggio, essere un mendicante, non più fantastico né pittoresco, che di quando in quando sporge una nota diplomatica ai passanti sul mercato politico, e quelli ridono: essere un cameriere che chiede la mancia a quelli che si levano satolli dal famoso banchetto delle nazioni, e quasi sempre, con la scusa del mal garbo, la mancia gli è scontata in ischiaffi. Quando sarà promosso a sensale o mezzano? La gloria delle storiche città è sostenuta dai ciceroni e da gente di peggior conio. Le più belle fra esse sospirano al titolo e alla fama di locande e di postriboli dell’Europa. E la plebe contadina e cafona muore di fame, o imbestia di pellagra o di superstizione, o emigra. Oh menatela almeno a morire di gloria contro i cannoni dell’Austria o della Francia o del diavolo che vi porti!”.

(And in that year [1866] Italy was inoculated with dishonor: that is, the mistrust and contempt of itself, discredit and contempt of other nations. These words that I write are dreary, I know. But I also know that for a people named by Italy it is not life to be physically harvested for making money economically, and to have neither an idea nor a political value, to represent nothing, to count for nothing, to be in Europe what the Fool is in the game of tarot: worse, being a beggar, no more fantastic or picturesque, than from time to time a diplomatic note goes to the passers-by on the political market, and they laugh: being a waiter asking for a tip from those who sat down to the famous banquet of nations, and almost always, with the apology of stomach-ache, the tip has taken him in the pits. When will he be promoted to intermediary or procurer? The glory of the historic cities is sustained by the tourist guides and people of the worst sort. The most beautiful of them sigh in their titles and fame at the inns and brothels of Europe. And the ignorant country folk die of hunger, imported malaria or superstition, or they emigrate. Oh let him at least die of glory against the guns of Austria or France than of the devil you bring!) (6).

Twenty years after 1866, other criticisms were heightened by his condemnation of Italian politics, its rulers and the Papacy. One of them was “put into scenes”, so to speak, through the tarot: it is a satire entitled “Il Nuovo Giuoco dei Tarocchi” (The New Game of Tarot), inserted in the Almanacco della Commedia Umana per il 1886 (Almanac of the Human Comedy for 1886) edited by Sanzogno. In twenty-two unnumbered pages, each of which is dedicated to an Archangel Major, are satirized, across two quarters and an illustration, personalities and political or social situations of Italy of the time. The identity of each Arcana is understood through the quatrains

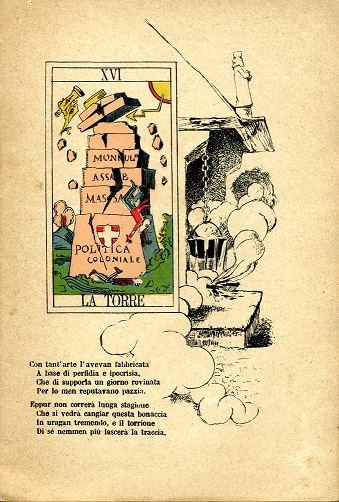

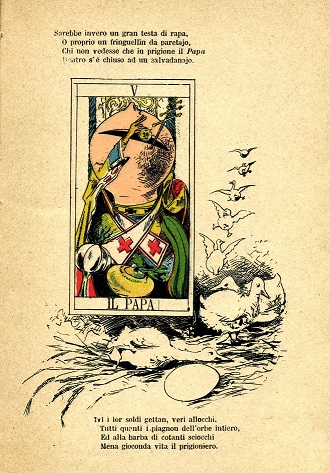

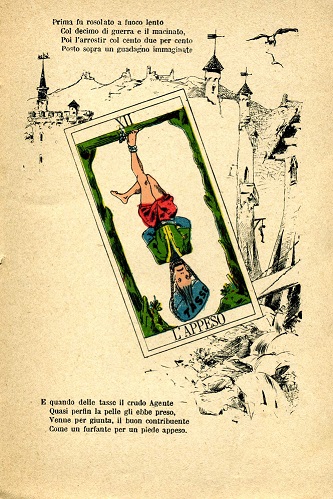

The Bagatello[Magician]was associated with Agostino Depretis, Prime Minister at the time; The lines accompanying the card of the Pope (Leo XIII) appear like a heavy accusation of radical mold to the Vatican's wealth; the card of the Emperor criticizes Paschal Mancini, Foreign Minister, rewarding Italian reintegration to Austria and Germany; the Hanged Man becomes the good taxpayer, especially those of the tithe of war and the grinding of grain. Particularly expressive are the verses accompanying the Tower card against the colonial policy of the government, which occupied the Bay of Assab in 1870 and that of Massawa in 1885. Prophetic verses, we would dare to say, as they anticipated the defeat of Italian ambitions in Eritrea, which happened just a year later at Dogali on January 25, 1887. Below, the verses and illustrations relating to the Tower, the Pope and the Hanged Man.

LA TORRE

Con tant’arte l’avevan fabbricata

A base di perfidia e ipocrisia,

Che di supporla un giorno rovinata

Per lo men reputavano pazzia.

Eppur non correrà lunga stagione

Che si vedrà cangiar questa bonaccia

In uragan tremendo, e il torrione

Di sé nemmen più lascerà la traccia.

THE TOWER

With so much art they built it

Based on perfidy and hypocrisy,

To suppose it ruined one day,

To say the least was reputed madness.

Yet not much time will pass

Before we see this calm weather change

To a tremendous hurricane, and the tower

Of itself will leave no trace.

IL PAPA

Sarebbe invero un gran testa di rapa,

O proprio un fringuellin da paretajo,

Chi non vedesse che in prigion il Papa

Dentro s’è chiuso in un salvadanaio.

Ivi i lor soldi gettan, veri allocchi,

Tutti quanti i piagnon dell’orbe intiero,

Ed alla barba di cotant sciocchi

Mena gioconda vita il prigioniero.

THE POPE

He would be in truth a great head of turnip,

Or precisely a little chaffinch in an open-air trap [whose chirping attracts other birds to come and be captured],

One who did not see that in his prison [Rome, encircled by Italian militias] the Pope

Is enclosed in a piggy bank.

They throw him their money, real allocations

All those pinions of the whole orb [world],

And by the beards of such fools [And dragging such fools by the beard]

The prisoner leads a carefree life.

L'APPESO

Prima fu rosolato a fuoco lento

Col decimo di guerra e macinato,

Poi l’arrostir col cento due per cento

Posto sopra un guadagno immaginato

E quando delle tasse il crudo Agente

Quasi perfin la pelle gli ebbe preso,

Venne per giunta, il buon contribuente

Come un furfante per un piede appeso.

THE HANGED MAN

First he was browned on a slow fire

With the tithe of war and ground grain,

Then roasted at one hundred two percent

Placed above an imagined profit

And when for taxes the harsh Agent

Almost completely had taken his skin,

He was also a good contributor,

Like a rogue hanging by one foot.

Notes

1 - See the essay Tarot in Literature I

2 - See the essay From ‘Barocchi’ to ‘Tarocchi’.

3 - Giosuè Carducci, Giambi ed Epodi, Prologo [Ambics and Epodes, Prologue], vv. 19-34.

4 - Ibid, “Il Canto dell’Amore” [The Song of Love], vv. 109-120.

5 - Ibid., “Per Eduardo Corazzini, Morto delle ferite ricevute nella Campagna Romana MDCCCLXVII” [For Eduardo Corazzini, Dead of wounds received in the Roman Campaign of 1867], lines 13-31

6 - Giosuè Carducci, “Confessioni e Battaglie, Serie Terza” [Confessions and Battles, Third Series], Giambi ed Epodi, Rome, Publishing house A. Sammaruga, 1884.

Copyright by Andrea Vitali - © All rights reserved 2017