Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, March 2015

Little is known of the life of the Galician xograr (1) Pedro Amigo (? - shortly after 1302), author of 36 Cantigas, plus three tensons [combats] and a pastorale. Documented as a canon in Oviedo and Salamanca, he would seem to have been born in Betanzon, something however that is still not certain. His work as a writer of cantigas - four of amor (love), (2) ten of amigo (friendship) (3), along with eighteen Cantigas of escarnio (mockery) and of maldizer (cursing) – was developed at the Castilian court of Alfonso X El Sablo (The Wise), who promoted the drafting of numerous cantigas, among which the most famous are represented by songs of worship dedicated to the miracles of the Virgin Mary (Cantigas de Santa Maria) for the most part set to music.

The Cantigas of Pedro Amigo, in the codex reported as Pedr'Amigo de Sivilha, reflect a different theme: they are in fact cantigas of escarnio (mockery) that together with those of maldizer (cursing), represent a satirical subtype of medieval Galician-Portuguese lyric called ‘trovadorismo’ that is expressed in Portugal between the end of the 12th century and the last years of the 15th, derived in part from Provencal sirventes but more from the Latin comic tradition. The two different typologies are distinguished in the first by the use of innuendo and occult words addressed to mo 'of satire to characters not explicitly named, and in the second by evidence of insults directed to specific persons who are even named. Regarding this second type of composition, Pedr'Amigo was one of the most tenacious and pungent scoffers of Maria Pérez, called Balteira, a famous Galician soldadeira (dancer) who stayed a long time at the Castilian court, while he hurled repeated darts against the Galician trovador Pero d 'Ambroa for not being able, together with Johan Baveca, to lead a battle in the Holy Land during the crusade launched by Jaime I of Aragon (c.1269), failing miserably.

The language is the primitive Galician-Portuguese, from which will derive the following modern one. It is not only a language cultivated by the Portuguese troubadours, but also by many Iberian poets and which found its highest expression in the above mentioned Cantigas de Santa Maria, to succeed in becoming the principal language of the cultured Castilian lyric of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The lyrics of the Portuguese troubadours, including Pedro Amigo, have come down to us in three key codices: the Canzoniere [Songbook] of the Palace of Ajuda, composed around 1280 in the time of Dom Dinis, King of Portugal; the Canzoniere of the National Library of Lisbon; former Colocci-Brancuti, and Canzoniere of the Vatican Library, Vat. lat. 1201, both dated 1525-27. The latter were copied in Italy, probably from a codex compiled in the first half of the 14th century by Pedro of Portugal, Count of Barcelos. Overall, the Galician-Portuguese lyric corpus includes about 430 texts of various types of Cantigas.

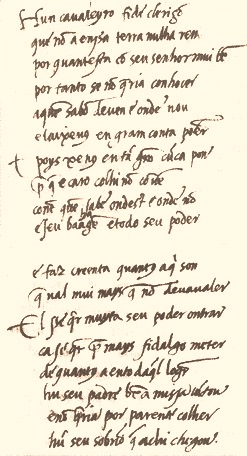

Of Pedr'Amigo de Sivilha what attracted our attention was the cantiga d’escarnio Hun cavaleyro, fi 'de clerigon (A Knight, son of a cleric), which in the following we report in full from the Vatican Codices (4):

Hun cavaleyro, fi’ de clerigon,

que non á en sa terra nulha ren,

por quant’ está con seu senhor mui ben,

por tanto se non quer já conhocer

a quen sab’ onde ven e onde non, 5

e leixa-vus en gran conta põer.

E poys xe vus en tan gram cunta pon

por que è tan oco, lhi non conven

contar quen sabe / ond’ est’e onde non

e seu barnagen e todo seu poder, 10

e faz creent’ a quantus aqui son

que val mui mays que non dev’ a valer.

El sse quer muyt’ a seu poder onrrar,

ca se quer por mays fidalgo meter

de quantus á en tod’ aquel logar, 15

hu seu padre ben a missa cantou,

e non quer já por parent’ acolher

hun seu sobrino, que aqui chegou.

The cantiga speaks about a man, son of a cleric, then lower class, who did not possess in his country any goods, but that in the land where he had come, he gave the understanding that he was the most noble of all, because people did not know who in reality he was and where he came from. The barb of the poet is directed against this man not because he was held in higher esteem than he should have been, given that those who knew him knew of his modest origins, but for refusing to recognize as a relative his recently arrived nephew, which according to him would have discredited the nobility of his lineage.

Of our interest are the words recorded in verse 8, "por que è tan oco" that is, "because he’s so crazy," an assessment that highlights the paucity of the fake knight. Giovanna Morroni, in a critical edition of our poetry (5), emphasizing the significance of oco as "louco, desvairado, vaidoso" that is "crazy, frenetic, vain" interprets the meaning of verses 7-10 thus: "and after being held by you in great account (consideration), because he is so conceited (presumptuous, foolish [folle]) it does not suit him for them to recognize that he knows from where comes his lineage and all his power" (E poys xe vus en tan gram cunta pon / por que tan è oco, lhi non conven / contar quen sabe / ond' est'e onde non / e seu barnagen e todo seu poder, ...) (6).

As said, the text presented by Morroni is that transmitted to us from the Vatican’s Portuguese Canzoniere of the sixteenth century. A diplomatic transcription was made of the same composition (7) by Monaci (8), and a semi-diplomatic one (9) making reference to the version in the Portuguese National Canzoniere, by Paxeco-Machado (10). Other transcripts are by Theophilus Braga (11) and M. Rodriguez Lapa (12).

The philologist and professor Elza Fernandes Paxeco (1912-1989), along with her husband José Perdo Machado (1914-2005), historian, philologist, dictionarist and bibliographer, both professors of philology at the University of Lisbon and Coimbra, are considered among the greatest Portuguese philologists. Their numerous transcriptions of ancient texts are still a point of reference for all scholars especially of Romance Philology.

We show in the following the facsimile of the cantiga (13) in the version in the Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional, antiga Colocci-Brancuti (14), with its textual reproduction below it, following the semi-diplomatic transcription made by the two philologists Elza Paxeco and Pedro Machado. Here we are offered several corrections, such as the separation of words in the manuscript that were united, writing in full the abbreviated words, in addition to the inclusion of the correct punctuation (15):

Textual reproduction:

Hun cavaleyro fidé clerigon

qué non a enssa terra nulha rem

por quantesta con seu senhormui ben

por tanto se non queria conhocer

aquen sabonde deuen é ondé non

e laixe vos en gram conta poër

E poys xe vos en tan gram cunta pon

porque e caro colhi non conuen

contra quen sabé ondest e ondé uen

o seu barnagen etodo seu poder

é faz creenta quantos aqui son

que ual mui mays que non deuavaler

El sséquer muyta seu poder onrrar

ca sé quer por mays figalgo meter

dé quantos a ento daquel logar

hu seu padré ben a missa cantou

ènon queria por parenté colher

hun seu sobrio que achi chegou.

Paxedo-Machado transcription (the underlined u must be understood as v)

Hun caualeyro, fi dé clerigon,

qué non a en ssa terra nulha rem,

por quant esta con seu senhor mui ben,

por tanto se non queria conhocer

a quen sab onde uen é ondé non 5

e laixe uos en gram conta poër,

E poys xe uos en tan gram cunta pon,

porque [h]e taroco, lhi non conuen

contra quen sabé ond est e ondé uen

o seu barnagen e todo seu poder; 10

é faz creent a quantos aqui son

que ual mui mays que non deu a ualer.

El ssé quer muyta seu poder onrrar,

ca sé quer por mays figalgo meter

de quantos a ento[n] d quel logar 15

hu seu padré ben a missa cantou,

e non queria por parenté colher

hun seu sobrio que achi chegou.

7. cuca

8. caro colhi

10. baagẽ, com há, ou rn sobre postoa aa

13. ontrar

18. achi=aqui

What caught our attention is the transcript that the two philologists give of v. 8, where with the critical-philological criterion they replace the expression 'caro colhi’ that appears to have no effect (16) with '[h]e taroco', a term which, as we have highlighted in our essays (17), means crazy [pazzo], foolish [folle], insane [matto].

So, while for the exemplar of the cantiga present in the Vatican Codices, Marroni accepts v. 8 "por que tan è oco" (because he’s so crazy), philologists Paxedo and Machado in the exemplar of the Cancioneiros Nacional replace "caro colhi" with '[h]e taroco' (he [is] mad), creating a convergence of meaning.

While the modern Portuguese dictionaries attest that the word 'Tarouco', is used in the folk environment both as an adjective and as a masculine noun, to indicate someone who has lost his memory due to old age, amnesia, dementia, loss of one’s reason/ confusion, idiocy (Pop, Class grammatical: adjetivo and substantivo masculino: Que perdeu to memória por due to velhice; desmemoriado, transient, apatetado, idiota) (18), it must be said that the word usually used today in cultured Portuguese language with the meaning of crazy, foolish, is "taralhoco" with variant 'taralhouco' (19).

We believe that the origin of 'taroco' or 'tarot', as of 'Tarouco', must be derived from the Hispano-Arabic tar[a]h, in turn derived from the classical Tarh, a colloquial form for 'subtraction, deduction' [detrazione, defalco], a thing that stands on the sidelines, which takes away, then also 'defect, imperfection'. This derives from the Arabic verb Taraha, with the meaning of 'remove, subtract', in Italian 'tarate'. The words Tarochus and Taroch, which as we have seen in our other essays meant 'imbecile, idiot, crazy person' [‘imbecille, cretino, matto’], is equivalent to tarato, that is 'missing intellect', as the subject is in a missing state, deducting a certain IQ. Tarado instead is the term commonly used today in Spain to say that a person is crazy [pazza]. The term tara in Italy also indicates an anomaly or hereditary disease. In Spanish, we have instead the noun Tarea, again from the same Arabic root, with the same meaning expanded to draw, throw, assign (the cards?)’, But also 'vice, defect': "Es interesante que este mismo verbo también nos dio la palabra Tara en sentido de 'vicio, defecto' y por extensión a 'defecto físico o psíquico ... de carácter hereditario' oltra a “Defecto mancha disminuye que el valor de algo o de alguien" (20).

Federico Garcia Lorca wrote a famous poem, set to music and still sung by famous performers, entitled La Tarara, a term which in Spanish means 'Loco, de poco juicio' that is, 'mad [matto], crazy [pazzo], of little intelligence' (21). Let us quote the verses, with the translation in English:

La Tarara, si;

Tarara, no;

Tarara, niña,

que la he visto yo.

La Tarara yes,

la Tarara no;

la Tarara, girl,

I saw her mysef

Lleva mi Tarara

un vestido verde

lleno de volantes

y de cascabeles.

My Tarara wears

a green dress

full of ruffles

and jingling bells.

La Tarara, sí;

la tarara, no;

la Tarara, niña,

que la he visto yo.

La Tarara si,

la Tarara no;

la Tarara, girl,

I saw her myself.

Luce mi Tarara

su cola de seda

sobre las retamas

y la hierbabuena.

Show off to me Tarara

Your tail of silk

Among the [Scotch] broom

And the mint [peppermint].

Ay, Tarara loca.

Mueve, la cintura

para los muchachos

de las aceitunas.

Ah, crazy Tarara

Move your waist

For the boys

Of the olives [peasants that harvest the olives]

In conclusion, the semi-diplomatic transcription carried out by the two philologists in an attempt to reconstruct the original text of the 13th century. where obvious interpolations were found, stands as further testimony to the meaning of the word Taroco as insane person, fool, crazy person [matto, folle, pazzo]. An insertion that makes it go back to the end of the 13th century. To validate this are two great philologists who would not have transcribed taroco if they were not aware of an already existing term in that historical period (22). An hypothesis that is almost a certainty when you take into consideration the etymology of the name, attributable to the Arab-Hispanic civilization, to which, as we know, we owe the origin of a large number of terms integrated later into the vocabulary of Italian and altered to the morphology of our language.

Notes

1 - The xograr was a kind of minstrel able to compose verses, play instruments, sing, tell stories or legends, recite poetry, and sometimes perform acrobatics, mime, as well as other games and skills.

2 - The Cantigas de amor, transpositions into Galician-Portuguese of the Provencal Canso, speak of troubadors who, through a terminology derived from the feudal world, turn to the women loved, criticizing them for being rejected or disdained.

3 - The Cantigas de amigo are a unique genre of Galician-Portuguese works, of which there are examples in the literature of Provence. The personage narrating is always a woman and the love theme, while of great importance, assumes the elements of nature: the grass, the river, the sea, etc. The most famous composer in this genre was Martin Codax (13th cent.) with his Siete [Seven] canciones de amigo.

4 - Vatican Library, cod. Vat. Lat. 4803. The poem in question is marked by the letter V in 1201.

5 - Giovanna Marroni, Le poesie di Pedro'Amigo de Sivilha, Annals of the Istituto Universitario Orientale, Sezione Romanza, edited by Carlo Giuseppe Rossi and Enzo Giudici, July 1968, pp. 189-339.

6 - Ibid, p. 323.

7 - By “diplomatic edition” is meant the pure, simple and faithful transcript of the contents of a document, without any intervention to mediate the text, beyond the solution of abbreviations. The name comes from the discipline of diplomacy, for which it is essential to replicate faithfully diplomas and legal documents.

8 - Ernesto Monaci, Il canzoniere portoghese della Biblioteca Vaticana [The Portuguese songbook of the Vatican Library], Halle a.S., Max Niemeyer, 1875.

9 - By “semi-diplomatic” is meant a transcription less conservative than the previous one, but without any intervention seeking to modify the text, except in rare cases, on the basis of what it is believed that the author wanted to express (in such a case it is a critical transcription).

10 - Elza Paxeco Machado, José Pedro Machado, Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional, antigo Colocci-Brancuti, Riproduzione in facsimile e trascrizione [Songbook of National Library, former Colocci-Brancuti, reproductions in facsimile and transcriptions], Lisbon "Revista de Portugal", Alvaro Pinto, 1946-1964. Specifically, our cantiga shows the designation 'VII, no. 1689 '.

11 - Theophilus Braga, Cancioneiro portuguez da Vaticana [Portuguese songbook of the Vatican], Lisboa, Impr. Nacional, 1915.

12 - M. Rodriguez Lapa, Cantigas d’escarnio e de mal dizer dos cancioneiros medievais galego-portugueses, edição critical pelo [critical edition by] Prof. MRL [M. R. Lapa], [Vigo], Ed. Galaxia, 1965. Lapa thought that the poem, which is marked with the number 317, was missing a verse.

13 - Elza Paxeco Machado, José Pedro Machado, op. cit., Vol. VIII. The work of the two philologists reports, in facsimile reproduction, all the cantigas presented in the Cancioneiro.

14 - The Song Book [Canzoniere] of the National Library of Lisbon , better known as the ‘Canzoniere Colocci-Brancuti’ brings together different compositions in the Galician-Portuguese language. This collection was copied in Italy, from Portuguese medieval manuscripts, in 1525-1527 by Angelo Colocci (1467-1549), who enumerated individual songs, also drawing up an index for them. In the nineteenth century the manuscript became the property of Count Paolo Brancuti Cagli da Ancona, who later sold it to philologist Ernesto Monaci, who made a critical review (see our note 8). In 1924 the manuscript came into the possession of the National Library of Portugal in Lisbon. Recent studies have found that the original manuscript was copied by six different hands, using both Gothic and cursive script. Of the 1664 original songs, the manuscript retains only 1560. Among the lost three are those attributed to Pedro Amigo.

15 - Below is the Esplicação, that is, the explanation of the intervention that the two philologists made to the texts, as described at the beginning of the first volume: "The Canzoniere of the National Library of Lisbon (ex-Colocci Brancuti), despite being already in the Library for 22 years, had not yet been printed. It takes time, because its publication was considered of great importance for bringing to the public, for the first time in a full and accessible manner, the largest medieval Portuguese Canzoniere. The compositions are not coincident with those already published in the Vatican Canzoniere by Ernesto Monaci and transcribed diplomatically by his disciple Enrico Molteni and given the light of day by the Italian professor. However, even this partial edition has been exhausted and thus out of reach for the majority of readers. There are also reading difficulties present for non-specialists. In our edition will be found abbreviations that do not employ italics (1); we substitute upper-case and the contrary whenever the text demands it. At the same time we punctuate (put in punctuation) in accordance with the interpretation of the manuscript. For the rest we keep the spelling of the apograph except in the case of an obvious slip. In the notes what appears in the codex will be shown. In square brackets are the letters and words wrongly omitted in the manuscript. The words in italics correspond to those found underlined in the apograph; this criterion is adopted for all passages in these conditions, even when the traces (evidence) clearly reveal a later intervention. In the fragments of the Art de Trovar we indicate the lines of each column; through this process you can easily find in the manuscript the passage that you want to verify, as well as the word recorded in the glossary. Variants are transcribed. The notes made by Colocci will be reproduced in the comments of a literary, historical, linguistic, biographical character that must accompany this edition of Cancioneiro of the National Library.

(1) Cfr.: "All abbreviations and acronyms are resolved without the need to indicate another type of printing for letters substituted; only in case of doubt about the possible development of an abbreviation will letters substituted be underlined that in the edition will be shown in italic letters (font)", 'Normas de Transcripción y Edición de Textos y Documentos', p. 6, No. 13 (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas - Escuela de Estudios Medievales).

16 - Colhi (to be read 'cogli') is the first person singular of the past remote of raccogliere, pick up or collect, thus, raccolsi, picked up; thus “perché é caro io raccolsi” would be “Because it is expensive I picked it up" (?).

17 - Please read the essays About the Etymology of Tarot, Tarot Means Fool, and Theroco Wind.

18 - Dicionário online de português at link http://www.dicio.com.br/tarouco/

19 - Prof. Graça Videira Lopes, New University of Lisbon, informs us of the existence of a minstrel named Pedro Larouco whose compositions are present in the Cancioneiros Portuguese, and the possibility that the meaning of Larouco, beyond the place name, can be interpreted as “crazy” [pazzo], “insane” [folle], whereas the term 'louco' in Portuguese means just “crazy” ('loco' in Spanish).

Prof. Antón Santamarina, a member of the Executive Council USC (Instituto da Lingua Galega) of the University of Santiago de Compostela, has informed us that: "The Galician dictionary records the word 'taroco', but with the meaning of ‘piece of wood, piece of hard bread’ (trozo de madera, trozo de pan 'duro’), nothing with the meaning of 'crazy'. Based on the data, medieval lexicographers find nothing. This 'taroco' ('piece of wood', with the variant 'Tarouco') is very similar to the Castilian word 'tarugo', according to the DRAE: "1. m: Piece of wood or of bread, usually thick and short; with the secondary meaning of 4 m. coloq: Person of approximate understanding (= holding the hard head, which is clumsy, like a piece of wood) "(Person de rudo entendimiento = que tiene la cabeza hard, que es clumsy, como un trozo de leña). In the Leonese language there exists the variant 'taruco'. Portuguese dictionaries also recorded 'tarugo' (1721), which surely comes from the Castilian (1386). However, the similarity can be random and the relationship between the two words is hard to justify, because, 'taròco' has an open ò. In addition, the meaning 'lack of understanding' is modern".

In the Diccionario de hablas leonesas [dictionary of Leonese words] by Jeannick Lemen, indicated by Prof. Santamarina, on "tarugo” we find that its meaning is close to similar in different Iberian regions: "normalemente son tres y también se llaman tarucos, machorras', 'persona muy brute or pocas de luces' (Gordaliza, 1988, 209); Nav. [Ribera, Pamplona, Central Zone]: tarugo, torpe [clumsy, inept, stupid], zoquete [dimwit, blockhead, block of wood], obtuso; [Ribera]: 'persona pequeña y gorda' (Iribarren, 1984)". Thus identified as 'tarugo' are: "very bad person or of little splendor (less intelligent) – chump [zuccone, in Andrea’s Italian], clumsy [goffo], dull [ottuso] – small and fat”.

It is our opinion that since the meaning of 'taroco' or 'Tarouco' in Galician, namely "piece of wood, piece of hard bread", and is also found in the Castilian term 'tarugo' which also has "person of approximate understanding = one who has a hard head, who is clumsy, like a piece of wood" (in English “blockhead” that is also synonym of fool, idiot, as cited by www.thesaurus.com) the term must unquestionably be correlated with the meaning of 'taroco' as a person deducted, who lacks a decent IQ (the dull blockhead [zoquete] quoted by Lemen), to be identified as a crazy person, since hard heads do not reason. See in this respect what we have written in the text about the etymology of 'taroco, tarot, Tarouco'. In addition, if as affirmed by Professor. Santamarina, 'tarugo' comes from the Castilian (term documented in 1386), it is very likely that it is to be derived from 'taroco' which needed to be already present for some time. As the philologists know, words travel and emerge capriciously.

20 - See: Real Academia Espanōla, Diccionario de la lengua española, Entry: tara, online al link

http://buscon.rae.es/drae/srv/search?id=tlmpG6d88DXX2zNWLiDE|8iKi5vsvrDXX2zBglnxk|psxYhxceZDXX2r275Dhg

21- We owe this information to Marcos Méndez Filesi, partner of the Association.

22 - Our assertion is based on the conviction of the great philological culture of Elza Paxedo and Pedro Machado. Obviously we need to be cautious because we are aware that errors in this regard have not been lacking: for example the indications that Cortelazzo gave for the expression "the devil is tarocco", attributed to Sacchetti, in fact belong to Saccenti and are therefore incorrect (Manlio Cortelazzo - Paolo Zolli, Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana [Etymological dictionary of the Italian language], Bologna, Zanichelli, 2004). Read in this regard our essay Tarot in Literature I.