Copyright by Andrea Vitali - © All rights reserved 2008 and 2016

Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, March 2015

"Sometimes I consider that the inventor of the cards was more ingenious than is supposed, because he not only made sure that the virtues, justice, temperance, fortitude, coins, sticks and similar things vie together to see which among them has more merit, the one winning and the other remaining won, but did more than that, given that the fool has an honored role in this game " (Original text: Considro alle volte che l'inventore delle carte fosse uomo più di quel che si stima ingegnoso, poi che non solo fa che le virtù: giustizia, temperanza, fortezza, danari, bastoni, e simili cose giostrino e insieme chi di loro più si vaglia contendono, l'un vincendo e l'altro rimanendo vinto, ma fatto ha di più, che 'l pazzo abbi in cotal giuoco onoratissimo luogo).

Ortensio Lando, Paradossi (Paradoxes), 1543 (1)

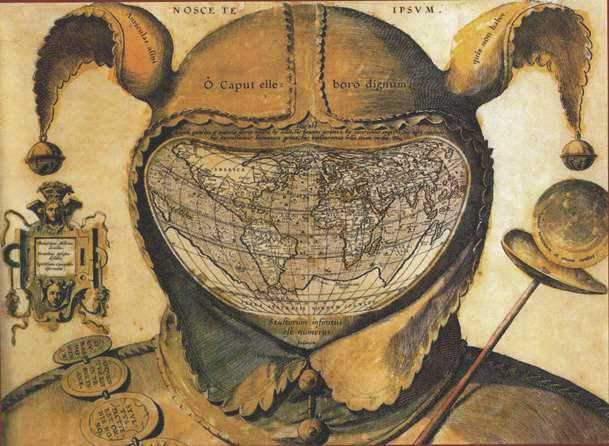

Ô Caput elleboro dignum (2)

- The World inside a fool head -

Geographic map of the world attributed to Orontius Fineus (Oronce Fine), 1590

The first known document in which the term Tarocho appears in relation to card games, is a literary text by anonymous called Barzelletta (Brescia, c. 1502) (3);

…Si a tarocho ho già giocato

Mai mi vien el bagatella,

Mai el mondo māco el matto

Ne giustitia meschinella,

Langiol mai con sua favella

Non mi vien a visitar.

Maladetto sia il giocar.

The second an accounts register of the Este Court of the second semester 1505, in a note dated June 30th. Then it appears again in the same register on December 26th. The French word ‘taraut’ appears for the first time in the same month of December 1505, in the city of Avignon, then part of the Papal States. Dropping a final “-ch” sound is common in French words that borrow from Italian.

In Giovan Giorgio Alione's Frotula de le dòne (Frottola of women), which we have identified (4), dated "toward 1494", which in the context of Charles VIII's descent into Italy, means the end of 1494 or a little later, the word Taroch appears with the meaning of "Foolish".

Marì ne san dè au recioch

Secundum el Melchisedech

Lour fan hic. Preve hic et hec

Ma i frà, hic et hec et hoc

Ancôr gli è – d'i taroch

Chi dan zù da Ferragù

To understand the word taroch in this work we have made use of the translation that Enzo Bottasso made of many words of the Frotula in the work edited by him, Giovan Giorgio Alione, L'Opera Piacevole (Giovanni Giorgio Alione, The Pleasant Work), where for taroch he gave "sciocchi" (foolish). So the verse with the word taroch, "Ancôr gli è - d'i taroch", must be translated as "there are still some fools".

Ross Caldwell has pointed out that the word tarochus, even if not referring to card games, was already used in the XVth century, as he discovered in the Maccheronea (dedicated to Gaspare Visconti, d. 1499), by the poet Bassano Mantovano, in which the term is used:

Erat mecum mea socrus unde putana

Quod foret una sibi pensebat ille tarochus

Et cito ni solvam mihi menazare comenzat.

(Ross’s translation: My mother-in-law was with me, and this idiot thought he could get some money out of her, so he started threatening me). Here “idiot” is a generic term meaning “stupid or slow-witted person”, “madman”, “fool”, etc.

We have discovered that the sirocco wind, the wind believed to induce insanity, was called in the Renaissance Theroco Wind (5). This is attested by a sixteenth century document by an imitator of Andrea Calmo (Venice, c.1510 - therein 1571), playwright and comedian, in which the author, writing a letter to two of his acquaintances, recounts events that happened in the Veneto region which he had heard about or participated in personally. The letter has come to us in two exemplars that differ in some variations of extreme interest. One variant consists of replacing scirocho with theroco to indicate both the wind and its action in making people crazy.

The author refers to the gardener of the Carmelite friars (l'ortolan deli frati de i Charmeni), who, leaving on his horse loaded with three bags of lime to bring to the fair at Pentecost (cargo de tre [in the variant, ‘dodese’, i.e. ‘twelve’] miera de calcina per andar a le pentecoste), he came across twenty thousand Cordovan horsemen (se scontrò in vintimille cavalli de cordovani [number intentionally exaggerated]) lightly armed (armadi ala liziera), who, completely at the mercy of the sirocco wind [in the Italian tradition the wind from the south, hot and dry from the African desert, puts people out of their minds] were commanded (i.e. pushed) by it (che per comandamento de scirocho and in the variant, che per comandamento de theroco), to make raids (erano sta comandati che scorsegiasseno) in the streets and alleys of the periphery (de la tangerlina). The gardener faced them with insults (li assaltoge con le pestenachie) and other ridiculous actions (facendo capriole [doing somersaults]), thus saving his life.

As previously expressed, the second copy of the letter replaces scirocho with theroco to indicate the wind’s action in making people crazy, so that the term theroco must be put in relation with madness, with becoming crazy, thus supporting what we have previously expressed on the etymology of the word Tarot [Tarocco].

Sciroccato ia said of a person who is stupid, confused, crazy, as if his brain were in the throes of a severe wind storm. The sea storm caused by the sirocco is in fact called by the term sciroccata, formerly the Noto, which in all probability gave rise to the concept of sciroccato (6).

But it is not only necessary to go back to this meaning: based on historic variants of 'tarrocco' or 'tarroco', it is also necessary to assess the term under its ludic [i.e. game-playing] aspect, attributing in this case the meaning of attack with cards stronger than those played by opponents, as with the expression 'ti arrocco, t'arrocco, ti arroco' = in chess, ‘I castle you’ [i.e. I force you to castle, but more general: “I force you to take shelter”]. It was intended to remind the adversary that one had played a winning card that put the other on the defensive (7).

And yet it must be said that the term Tharocus should also be connected to Bacchus, in reference to the madness that characterized the orgiastic rites held in his honor (8).

It is thus a term understood with polysemic meanings, that is, expressing several meanings, according to a widespread practice in the Renaissance period.

The assignment is thus inspired by a card of the deck, not an unusual situation, in that the Tarocco in Liguria, Tuscany, and Sicily was called by the term Ganellino or Gallerino - that is, the Bagatto [Magician] - as we have shown thanks to our discovery of a treatise on the game of Minchiate (9).

Recently, the word Tarocco had meanings attributed to it dictated more by assumptions than certainty, as were the attributions advanced by the authors of the sixteenth century, basically in conflict with one another. One might wonder why the men of the sixteenth century did not have much clarity about the meaning of 'Tarocco'

Some of them had intuited that it somehow had to be put in relation with madness, such as Lollio: “quel nome bizzarro / Di tarocco, senza ethimologia, / Fa palese a ciascun, che i ghiribizzi / Gli havesser guasto, e storpiato il cervello” (that bizarre name / of tarot, with no etymology, / that shows everybody that oddities / had wasted and mangled his brain), or Berni: “viso proprio di tarocco colui a chi piace questo gioco, che altro non vuol dir Tarocco che ignocco, sciocco, balocco…” (... the proper face of tarot is of one whom-this game pleases, that no other may be said of Tarot than ignorant, foolish) (10).

The problem was obviously haunted by an etymological misunderstanding of the term 'tarocco' - today considered by philologists a word of vulgarized Lain (11) or dervided from Arabic (12) - so much so that Francesco Vigilio, called Francesco Mantovano, attributing to the term a transalpine source, says in his dialogue Italy and Mantua (1532-34), "But now with the barbarian rite, without relationship to the Latin, they call it Taroch" (Barbaro ritu, taroch nunc dicunt nulla latina ratione) (13). This suggests that in reality few people knew its real meaning, except the one who had given it the name, including his or her circle of friends.

Probably some players would have connected the term to the expression “ti arroco”, i.e. “I force you to take shelter”, as mentioned above, which at first glance would seem the most appropriate interpretation given its phonetic immediacy. But to the majority of those who were playing tarot, the meaning was unknown and indeed hardly indispensable to them. That is not surprising: if today you were asked the meaning of the terms 'briscola' (the name of an Italian card game) or 'poker', only a few experts on the history of card games could answer (14).

So today we are aware of a meaning that from the Renaissance until recently was basically unknown to everyone, that with the word Tarocco came its being identified, in addition to the above, expressed in terms of symbolic polysemy, with the card of the Fool, or folly in general. A good reason, we could say, given that madness pervades the entire group of the Triumphs (Major Arcana). A colorful Madness, connected on one side purely to the aspect of game-playing and on the other to the concept of sensible and senseless madness, according to the ethical principles of the Christian religion.

Regarding the game-playing aspect, it must be said that the Fool card may be worth everything or nothing - as it is also in philosophical terms: it is not taken and cannot take other cards, is different from all, as different as madness was considered by society of the time, defined by Ripa in his Iconology as follows: "Non è altro l'esser pazzo, secondo il nostro modo di parlare, che far le cose senza decoro, e fuor dal comune uso degli uomini per privazioni di discorso senza ragione verosimile o stimolo di Religione" (Being mad, according to our manner of speaking, means nothing but doing things without dignity, and outside of the common use of men, due to lack of discourse with credible reasoning or the stimulus of Religion) (15).

And it is of this latter sense that we inform you briefly on the concept of sensible and senseless madness, which permeates the entire structure of the Triumphs (Major Arcana) (16): senseless madness, which is the pursuit of pleasure, success and material goods, leads people to destruction; sensible, to mitigate his loneliness, accepting God and working to conform to His holy will: Homo sanctus in Sapientia manet sicut sol, nam stultus sicut moon mutatur (Ecclesiastes 27, 12) [Douhy-Rheims literal translation: A holy man continueth in Wisdom as the sun: but a fool is changed as the moon].

The thought of Scholasticism, which aimed to confirm the truths of faith through the use of reason, grouped in this category all those people who didn’t believe in God, even if able to reason. In the tarot the presence of the Fool has therefore a further and deeper sense: the Fool, in its meaning of unbeliever in God but possessing reason, had to become, through the teachings expressed by the Mystical Staircase, the "Fool of God", as the most popular saint became, that is, St. Francis, who was called “The Holy Minstrel of God” or “the Holy Fool of God" (None was more beautiful, / More joyful, or greater, / Than he who, by zeal and love, / Became the fool of Jesus") (17).

Medieval and Renaissance man will live this reality: being mortal, everything for which he labors is vanity, and folly to pursue; but because all men seek in some way their well-being, all are foolish, because only in God is true happiness. The only remedy is the pursuit of sensible foolishness, for all is vanity, including the Wisdom of the World: "The fourth Vanity, which belongs to ambition or pride for one’s life, is Worldly Wisdom, of which the Apostle says: The wisdom of this world is foolishness unto God. And if it is foolishness, so it is a great vanity to delight in it, and take so much pride in the same, as the Worldly do, especially against the Wisdom of the same God and His saints. And it is strange and marvelous to see how contrary God’s Judgments are to those of the World. Who would not believe that the Worldly were the most likely to render service to Jesus Christ in his Church? Yet the Apostle says: Non multi sapientes secundum carnem: God has not chosen many wise men after the flesh. Who would not believe that a Worldly Wise person would make a Wise Christian? Yet St. Paul says no to him until he becomes a fool: Stultus fiat ut sit sapiens: If anyone among you is wise, let him become a fool, in order to be wise. Vain and therefore of no account is the Wisdom of this World, if it is not subject to the Wisdom of God, for anyone who out of worldly regard, as seems important to him, condemns with the Wisdom of the World those people who condemn the world, and are resolved to serve God, absolutely on this account is merely senseless, and so he will confess one day, when he will exclaim in eternal pain with those of his condition: Nos insensati vitam illorum aestimabamus infaniam: We senseless ones judged the lives of the saints mad: now we see that they were prudent, and the rest of us mad. And this means, when the carnal Wisdom contradicts the spiritual, and not otherwise" (18).

Recites Ecclesiasticus (1-15): "Infinite is the number of fools", meaning that all men are fools. While Jeremiah says, "Every man is made foolish by his wisdom" (Chapter X, 15) and attributes Wisdom only to God and leaves foolishness to men (X 7 and 12). Turning to Ecclesiasticus (27.12), when it says "The fool changes like the moon; the Wise One like the Sun does not change", this means that all mortals are fools and that the title of Wise One belongs only to God. The Moon is identified by the interpreters with human nature; the Sun, source of all light, with God.

Erasmus in his Praise of Folly will say: "If he who is not wise is a fool, and if one who is good, according to the Stoics, is also wise; foolishness of necessity is the heritage of all men" (19).

Significant in this regard and of the era in which the tarot triumphed throughout Europe is this Song of Madness [Canto del Pazzia] (20) attributed to Giovambattista dell'Ottonajo (1482-1527), herald of the city of Florence, in which every category of people is declared mad [pazza]. All mortals, without exception, belong to the family tree of Madness:

SONG OF MADNESS

That which deeply punishes

Our superb madness

Wants us now to show to all the world

That all have a branch of Madness

Crazy [pazzi] indeed are all the lovers,

Because they are always the people’s jokes;

Crazy all the Soldiers

Who go to die for almost nothing;

Crazy is each one living

But even crazier is the one who would hide his madness.

Crazy are all the Princes and Lords,

Being able to stay in peace but wanting war;

Crazy, Historians and Professors,

Who consider crazy even those who don’t do wrong;

Crazy those who believe that on earth

There is someone who is without madness.

Clerics all of them crazy

For the mad ambition that reigns in them;

Crazy all the Merchants,

Because their goal is always gold.

Crazy is he who with treasure

Thinks to hide his madness.

Crazy the Common People and all the Craftsmen,

Who expect to live richer receiving aid and gifts;

Crazy are the servants and the peasants

Who labor that their masters may live well.

Crazy is one who lives in festivals and music

And those who complain too much of his madness.

Crazy is he who wears himself out and spends money

To give pleasure to the ungrateful and envious;

Crazy is he who criticizes others

Without first having shown his own works;

Crazy is one who wants to know

More things other people, rather than his madness.

Crazy are those who believe too much and love too much,

And crazy those without faith or love;

Crazy is one who accuses himself

That others may have usefulness and honor.

Crazy is he who thinks to cover

His mistake with madness.

Crazy are those who never think about things

And those who think so much that their brains melt;

Crazy is the one who gives to others

Without measure and remains himself in his underwear [still poor]

But craziest is the one

Who unites malice to his madness.

Crazy all women, changing at every wind,

Which is death to those who love them;

Crazy is one who lives at Court,

and then dies in hardship in a ditch.

Crazy is one who hopes to live content

In the middle of all the madness.

But although madness is a sweet thing,

And the more you have, the less you think you are infected,

He who rules and is in Heaven,

Does not want us to say

That all our faults

Can be excused by madness.

The tree of Madness spreads its branches

Over all mortals, which includes

The young, the beautiful and the ugly,

and the Old, and Women; and each sometimes takes

Small branches and leaves;

Those who embrace the tree, and those at its top, have the [whole] Madness.

Original text:

CANTO DELLA PAZZI’A

Quel, che la nostra superba pazzía

Punisce nel profondo

Vuol, ch’ oggi noi mostriamo a tutto’l Mondo,

Che ciascuno ha un ramo di Pazzía.

Pazzi tutti son ben gl' innamorati,

Perchè son sempre il giuoco della gente;

Pazzi tutt’i i Soldati,

Ch’a morir vanno quasi per niente;

Pazzo è ciascun vivente,

Ma più chi vuol coprir la sua pazzía.

Pazzi son tutt’i Principi, e Signori,

Potendo stare ‘n pace, e voler guerra:

Gli Storici, e’ Dottori,

Che tengon pazzo spesso chi manco erra:

Pazzo chi crede in terra

Non aver questo ramo di pazzía.

Pazzi li Religiosi tutti quanti

Per la pazza ambizion, che regna in loro:

Pazzi tutti i Mercanti,

Perché sempre il lor fin pongon nell’oro.

Pazzo chi col tesoro

Pensa di ricoprir la sua pazzía.

Pazza la Plebe, e tutti gli Artigiani,

Che speran da’ più ricchi ajuti, e doni;

Pazzi i Servi, e’ Villani,

Che stentan, perchè godano i Padroni;

Pazzo ch’in festa, e’n suoni

Vive, e chi troppo piagne sua pazzía.

Pazzo chi troppo s’affatica, e spende

Per dare a ingrati, e ’nvidiosi piacere:

Pazzo chiunque riprende,

Senza far prima l’opre sue vedere:

Pazzo chi vuol sapere

Più i casi d’altri, che la sua pazzía.

Pazzo chi troppo crede, e chi tropp’ ama,

E pazzo chi non ha fede, nè amore;

Pazzo chi sé diffama,

Per far’ad altri ed utile, ed onore:

Pazzo chi ‘l suo errore

Si crede ricoprir colla pazzía.

Pazzo chi mai a’ casi suoi non pensa,

E chi troppo in pensar stilla il cervello;

Pazzo chi ‘l suo dispensa,

Senza misura, e resta poi l’uccello;

Ma peggior pazzo è quello

Ch’unisce la malizia a la pazzía

Pazze tutte le Donne, che la morte

Son di chi l’ama, e volte ad ogni vento;

Pazzo chi vive in Corte,

Per morir n’una fossa poi di stento:

Pazzo chi quà contento

Spera di stare in mezzo alla pazzía.

Ma benché la pazzía sia dolce cosa,

E chi più n’ha, men si conosca infetto:

Quel, che ‘n Ciel regna e si posa,

Vuol, che da noi, che ‘l proviam vi sia detto;

Ch’ogni vostro difetto

Non fia da lui scusato per pazzía.

Stende i suoi rami sopra i mortal tutti

L’Alber della Pazzía, e di quel coglie

Giovani, belli, e brutti,

E Vecchi, e Donne; e ciascun poi ne toglie

Chi ramucci, e chi foglie,

Chi l’abbraccia, e ch’ in cima ha la Pazzía.

Only a mind purified of the passions was able to pursue sensible madness. A folly that is greatly distant from that of worldly men by nature evil. A distance that this satirical passage from the comedy The Fair, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, the Younger, presented at Carnival of 1618 in the "Theater Hall of Ufizi", well expresses:

Act Five – First Day - Scene Eleven (21)

Chorus:

I do not know if the world will suffer greater damage

From fools or from evil men,

Because everywhere I turn to look

My dubious judgments

Accompany my raving gaze:

Nor stop their flight nor have any peace.

I look for the strange way of the Fool:

And I see him wandering aimlessly like a horse without a bridle,

That runs through forests and mountains,

And those fields and those harvests,

And those meadows and those springs

Where Ceres flourished, and Diana lay

Remain deserts to that insane frenzy. [in the sense that the Fool does not consider them].

I turn to the other side

And I see that the wicked one ignites the lure

And because of his blameworthy fires

Rises into the sky such a flame

That it destroys countryside and villas.

Astrea [Justice] goes away

Exiled from the world: Wrath triumphs and Mars [war] reigns.

From Phoebus [Sun, truth] finally arrives to me

In thought the sentence that I express quickly

With a wisdom derived from his frenzy

Truer conclusions,

Because against an evil heart

Punishment and torment are little help (i.e. an evil heart does not change even if it is tormented and suffers pain)

And for the Fool snares and chains do not help (i.e. to change the Fool snares and chains do not help)

A person taking Leave of the CHORUS

O ladies, even if those crazy frenzied ones that you see here

are enclosed within the walls [of the Madhouse],

do not believe yourself safe, any of you,

from assaults unbridled and stormy;

Because if you expose yourself to fate,

there will be some clever men

whose ambition is for you to fall prey to them.

They will throw themselves into the streets like murderers.

Original text:

Coro

Onde maggiore il danno

Abbia il mondo io non so, se dagli stolti,

O dagli uomini rei;

Che dovunque io mi volti,

Dubbj i giudizi miei

Dietro lo sguardo vaneggiando vanno:

Né ferman l’ali, e posa ancor non hanno.

La via ricerco strana

Del folle: e ‘l veggo errar giumento sciolto,

Che selve scorre, e monti;

E quei campi, e quel colto,

E quei prati, e quei fonti

Ove Cerer fiorì, giacque Diana.

Restar deserti a quella furia insana.

Traggomi all’altra parte,

E ‘l malvagio vegg’io che l’esca accende,

E di sue ree faville

Tal fiamma al cielo ascende,

Che campagne, e che ville

Ne son distrutte: Astrea del mondo parte

Sbandita: Ira trionfa, e regna Marte.

Da Febo alfin mi viene

Sentenza nel pensiero, ond’io saetti

Saggio nel suo furore

Veracissimi detti,

Che contro un empio cuore

Scarsi di morte sono tormenti, e pene:

Nel folle bastan pur lacci e catene.

Uno del CORO licenziando

Donne, quantunque chiusi in quelle mura

Quei che vedeste or qui, pazzi furiosi,

Non si creda nessuna esser sicura

Dagli assalti sbrigliati e tempestosi;

Chè, se voi v'esponete alla ventura,

Ci saranno de' savj, che ambiziosi

Che la preda di voi loro in man cada,

Si getteranno assassini alla strada.

At this point, to conclude, we would like to emphasize the meanings of those multiple etymologies inherent in madness [pazzia], that today we evaluate under the common denominator of insanity [pazzia] or folly [follia], but in the past were characterized by precise meanings that revealed differences. We will do so by reporting in full, including notes, for lovers of these refinements, what in 1825 the abbot Giovanni Romani writes in this regard in his General Dictionary of Italian Synonyms (Dizionario Generale de’ Sinonimi Italiani), considerations that sometimes, as the author shows, are in sharp contrast with the words of the Vocabulario of the Crusca in the seventeenth century (22).

FATUO, STOLTO, SCEMO, SCIOCCO, STOLIDO, INSENSATO, STUPIDO, MELENSO, BALOGIO, BALORDO , STORDITO, SCIMUNITO, INSIPIENTE, INSIPIDO, INSULSO, INSANO, PAZZO, FOLLE, MATTO, DEMENTE, MENTECATTO, DELIRO, FRENETICO, MANIACO, FURIOSO, FORSENNATO, INTRONATO

These attributes relate to the morality of man, who, by some upset of his physical organization, cannot make regular use of the natural faculties of his mind, precisely the dictates of reason. We are accustomed to use some of them in ordinary speech as synonyms, but if they are submitted to critical comparison, they can introduce some notional differences, by which to distinguish one from the other.

Fatuo [f. fatua / pl.m. fatui - pl.f. fatue], (Lat. Fatuus) (1), is not defined by the Crusca, but only equated to Stolto and Scemo. The Stolto, as we shall see below, and as mentioned in this note, is properly One who, out of weakness [debolezza] or stupidity [ottusità, also translated as slowness, dullness, obtusity] of his senses [sensi], cannot judge judiciously; but Fatuo is One whose senses are so imperfect, he is powerless to judge. The Scemo, then, when applied to morality, as will be shown later is the one who has little sense. To Fatuo therefore, considered in the notion attested just now, can correspond the following examples: "Intentions fatue [fatuous] (meaningless, senseless), full of laughter, also tears" (Coll. Ab. Isac. 40); "They guard and are troubled with so much fatuitade [fatuity], so much good lost, etc." (Fior. S. Franc. 151), etc.

(1) The Latin Fatuus derived from the verb Fari (Prophesy), and among the ancient Romans, Vati, or Poets, were called Fatui from Fatu, a word originally from the Greek Phatyis (Vate, poet), but because the Poets prophesied when they were invested by furor [furore], then, metaphorically, the attribute of Fatuo was applied to the Pazzi or to the Furiosi. Among the Latins the Fatuo was distinct from the Stolto, because the first was regarded as devoid [privo] of sense, and the other only of dulled sense [sensi ottusi]. Fatuo by Terence was equated with Tarpo, Insulso [vapid] (Forcell, Lexic., Voc. Fatuus).

Stolto [f. stolta / pl.m. stolti - pl.f. stolte], Lat. Stultus, according to the Crusca, equals of little sense, and according to them is synonymous with Pazzo and Sciocco. Reserving the right to speak in their place of the notions of Pazzo and Sciocco, we agree with the Crusca that the lack of sense is precisely the element that constitutes Stoltezza, or Stoltizia, which is opposed to Wisdom, for, as is said, it is the Stolto who, because of weakness of Senso, or lack of understanding, cannot form correct judgments of things, nor operate wisely. Under this concept, different from that of the more pejorative Fatuo, can be understood Stolto in the following examples: "Nothing is as useful to the Stolto, as to serve a wise man [savio]" (S. Bern. Lett.); "There are many, who being very stolti, are made masters of others" (Bocc., Nov. 82 2).

Scemo [f. scema / pl.m. scemi - pl.f. sceme], is proprerly This that is lacking in some part of its fullness, or size (2), so it is said: Scema Measure; scema Moon; scemo Mountain (See Crusca). Considered therefore in the proper sense, Scemo has no affinity with Fatuo, or Stolto; but if the same is metaphorically referred to the mind, to denote the diminution or decrease of its faculties, then it approaches the intellectual notions of Fatuo and Stolto, with the difference, however, that Scemo is less pejorative than Fatuo, but is more so than Stolto, though the Crusca makes them of equal value. The aforementioned notion may be agreed upon with examples: "He thought Claudius the adornment of the age, and student of fine arts, but he was scemo" (Tac. Dav. Ann. 6, 126); "Because your scemo brain, and too much wine, makes you speak on the part of Appollino" (Ber. Or. 2, 1. 68). When the lack of wisdom comes from nature, man is called Scemo; when it is caused by the will, man is called Stolto; therefore Scemo is below Stolto.

(2) There are various opinions about the etymology pertaining to the origin of Scemo. Some deduce it from Lat. Semis (Half); others from the verb Eximere (Decrease); others from Xemum (Ferrar.,word Scemare [wane]). But it does not seem unlikely that Scemo originated from Lat. Cyma (Top end of plants) to indicate bodies that lack tops. Our villagers say: Cimo tree, one from which cima (the top) was taken off; and, by similarity: Cima barrel, one diminished from its fullness, etc.

Sciocco, or Isciocco [f. sciocca / pl.m. sciocchi - pl.f. sciocche], (3), when applied to the physical, is analogous to Scipito, [Tasteless], Insipido [Bland], etc., as will be shown in its place (see Scemo), and in this case has no affinity with the moral attributes as set out above; but when Sciocco (which happens frequently) is related to human actions, then, according to the Crusca, it applies to One who is lacking in wisdom and prudence. However, carefully reflecting on the applications that are used in attributing Sciocco, it is easy to see that it is primarily directed at intelligence, for example: "Wretched and full of vain and sciocchi imaginings" (Petr., Son. 204); so they say, sciocca intention; sciocco judgment, etc. If often the added Sciocco also applies to actions, this happens in a subordinate way, because Sciocco is said of those actions that result from inadvertence, lack of thought, lack of reflection, etc., mental defects, which are Sciocchezza, or Scioccheria (4). Under this notion Sciocco must be understood by the following examples: "He makes such sciocche laughter, etc." (Bocc., Nov. 21, 15); "I never made more of a scioccheria (sciocca action, that is, derived from unwise judgment)" (Fir. Luc. 3, 1), etc. From these considerations we can ensure that a Sciocco is one who is not already devoid or lacking in sense, as is the Fatuo or Scemo, but rather one who does not know how to make good use of hindsight [senso]; in that it is near Stolto, but in a lesser degree of neglect [trascuranza].

(3) What is called in Italian Sciocco is called Sot by the French, Sosa by the Spaniards, etc., without being able to determine the origin of it. To Ferrari it seemed possible that it originated from the Latin word Insulsus, or Stultus; but I do not see there a formal analogy (Ferrar., voc. Sciocco).

(4) Scioccaggine is also used, which is preferred to the other two, when s' intends to want to express A sciocca habit.

Stolido [stolid] [f. stolida / pl.m. stolidi - pl.f. stolide], Lat. Stolidus, applied to the physical is akin to Insensato, Stupido, etc., for example: "Worms from human bodies outside of these bodies seem dull [melensi] and stolidi ..." (Red. Oss. An. 127). However, referring to morality, for example: "Numantina, his first wife, was accused of making him stolido by sorcery " (Tac. Dav. ann. 4, 48), expresses the total deprivation of his mind, so its notion approaches very closely that of Fatuo, except that it seems to me that the Fatuo is without sense by nature, and that the Stolido has lost it by some accident.

To Stolido the Crusca makes synonymous the attributes Insensato and Stupido. Insensato, when referring to morals, according to the Crusca, means, One who does not have intellectual sense, and in this case can appear synonymous with Stolido, for example: "Because he was considered almost an insensato" (Fr. Sacch., Nov. 2), "Turpin in this calls him Insensato [without sense]" (Bern. 2, 19, 56); but when Insensato applies to brute animals, it seems to take the notion of Stupido, for example: "From Insensato animal ... you went to be a man" (Bocc., Nov. 41, 26). Indeed when being added it invests some action, takes the notion of Stolto or Sciocco, for example: "O insensate care of mortals” (Dant., Par. 11) (5).

(5) Thus one must not confuse Insensato, which expresses deprivation of the mind, with Insensible [Insensitive], indicating deprivation either of physical sensations or moral sensitivity.

Stupido [f. stupida / pl.m. stupidi - pl.f. stupide], Lat. Stupidus, of we talked about elsewhere (See Stupido, under the heading Attonito [Astonished]), is in relation to morality, expressing habitual imperfection of the intellectual faculties to conceive and judge things, coming closer to the notion of Fatuo and of Insensato, than to that of Stolido. But Stupido also means one who, taken of a certain lethargy, languishes immobile, or who, for lack of counsel, or any other cause which makes him slow, is alienated from sense, for example: "Stupido is the man whose sentiments do not control his operations" (But. Dant., Purgatorio. 4); "By the abundance of tears the confessor was all stupidito [stupified]" (Mir. Mad. M.). In this case the stupidity, as contingent and transitory, would differ from Insensatezza and Stolidità, which are conceived as permanent.

Melenso [dull] [f. melensa / pl.m. melensi - pl.f. melense], or Milenso (6), is not defined by the Crusca, but by them only declared synonymous with Sciocco, Scimunito, Balordo. But making observations about the examples that they attach, it appears to us that we can assert that Melenso qualifies one for dullness [ottusità) of wit, or weakness of temperament, one neither knows the value of things, nor feels inclined to them, for example "Xenophanes ... feeling ... like the proverbial milenso because he declines to want to gamble at cards, etc." (Sig. Pred. 8, 139); "Filomena ... in a milensa manner (by a little expedient) would not appear, etc." (Bocc., G. 1, f. 1), etc. But when such an adjective is applied to things, it can appear synonymous with Sciocco, Stolto, Insulso, etc., for example: "Always the bad and cowardly milensi (sciocci) thoughts have won" (Dittam. 1.7); "I have appeared ugly ... and what is more important without spirit and melense (insulse)" (Red. Lett. 1, 346).

(6) Of this word, Menagio, Ferrari, Murator made sugestions; but none of them was able to suggest a satisfactory etymology.

Melenso was by the Crusca made synonymous with Balogio, induced to this by the sole example of the vernacular composition: "There walked Ciuschéri, blind and balogi" (Buon. Fier. 2, 1, 14). It seems to me that in the aforementioned example Balogio was used for the figurative notion of Melenzo, since Balogio, or Balogia, which in our dialect is called Baleuss, is an attribute that applies to boiled chestnuts; and that is figuratively attributed to subjects of no value.

Balordo [f. balorda / pl.m. balordi - pl.f. balorde], Lat. Bardus, in accord with the explanation made elsewhere (see Balordaggine), is an attribute that applies to those who are of obtuse [ottuso], or slow, intelligence (7), for example: "To see you tire out behind a Balordo" (Car . Lett.); and under this notion Balordo approximates much to those of Stolido and of Insensato, not that of Melenso. But on the other hand this attribute is used more frequently to mean a certain passing confusion of mind, produced by some sudden accident, for example: "Psyche remained like a balorda" (Fir. As. 149); "Showing great surprise, I was standing like a balorda thing" (Ibid, 25); "Claudius, drunk and balordo, did not notice it" (Tac. Prev. 12, 260). Under this notion it seems to me that Balordo becomes akin to Stupido (8).

(7) In our dialect Balordo also applies to physical objects to indicate poor quality, for example: balordo wine; balorda meat; balordo lunch, etc., and also figuratively, saying: balordo sonnet; balordo sermon, etc.

(8) As synonyms of Balordo, the Crusca nods at Balocco, Minchione, etc.; these being, as it seems to me, of local origin, they do not deserve special explanation.

Stordito [Stunned] [f. stordita / pl.m. storditi - pl.f. stordite], (9), by the Crusca is made synonymous with Sbalordito, Astonished, Confused, because in reality this attribute includes all the notions of similar predicates; as you can gather from the explanation that Varchi put, saying: "Storditi properly are called Those who have fallen from lightning near them, standing amazed and sbalordito, who are also called intronati [dazed]" (10) (Ercol. 63). They remain, however, stunned not only by the nearby explosion of lightning, but from every other cause that has power to oppress sense and imagination, for example: "From being thus storditi [stunned ones] by their realization [of being discovered in bed], they were immobile ..." (Bocc., Nov. 82, 6); "Castruccio feeling this, and hardly believing, departed as one stunned [stordito] from Pistoia" (G. Vill. 9, 302); "I turn stunned [stordito] by fear" (Red. Annot. Ditir. 205); "Stupor [stupore] is a stunning [stordimento] of the soul, from seeing or hearing great and marvelous things, or sensing them in any way" (Dant. Conv. 198); "With his bestial cry he stuns [stordisce] other men and puts fear into them" (Fav. Esop.), etc. Then around the notions of Astonished, Confused, etc., which enter into the complex idea of Stordito, see the title Confused. By the above explanation the result is that Stordito is very similar to Stupido, from which, however, it differs grammatically, since this has the value of That has stupore, or that is taken by stupor, and that means Made, or Rendered stupid, so Stordito corresponds better to Istupidito [stupefied].

(9) Muratori (Antich. Ital., Voc. Stordire) rightly rejects the etymology suggested by Menagio and Ferrari around the origin of Stordito but he did not know what better to add. The French make Estourdi correspond to the Italian Stordito, which, according to Ducange, comes from Estour.

(10) I am of the opinion that the addition Intronato is actually what precisely agrees with that of the sudden burst of lightning, or some other sudden and strong noise that is offensive to one’s hearing; and it seems to me that such a word originated from the noise of thunder: "The terrifying thunder intronavano [deafened] the ears" (Serd. Hist. 3, 126); and similar. could be applied to those who for some sudden fright remain storditi [stunned], for example: "And with his mind stordita [stunned], intronata, etc." (Ber. Orl. 1, 12, 74).

Scimunito [f. scimunita / pl.m. scimuniti - pl.f. scimunite] (11), according to the Crusca, equals Scemo or Sciocco. It seems to me that this attribute is more akin to that of Scemo than Sciocco, because it mostly applies to Those who by either old age or other regular or special causes, were damaged or diminished in their intellectual faculties. Which you can confirm by example: "If the person knows or believes that the confessor is by old age, senile, or by disability, or natural condition, forgetful or scimunito" (Pass. 122).

(11) In accordance with what has been stated in the text, the opinion of Ferrari (Orig. Ling. Ital., Voc. Wane) seems adoptable, which drew the origin of Scimunito from Scemo or Scemato.

Insipiente [f. insipiente / pl.m. - pl.f. insipienti], Lat. lnsipiens, by the Crusca is said identical to Sciocco, but it seems to me that this differs in the fact that the Sciocchezza, just as we said, is the effect of lack of consideration and of inadvertence, but Insipienza is the effect of the lack or deprivation of knowledge. Indeed Insipienza, as the Crusca says itself, is the opposite of wisdom and consequently Insipience literally equals not wise, as results from the proper example: "More than happy to be a wise beggar, than a rich Insipiens" (Salvin. Disc. 1, 83). From Insipienza often originate sciocche thoughts, words, actions, not by this can it be asserted that it is equal to Sciocchezza.

It was then masterful to distinguish Insipiente from Insipido, because this refers mainly to the physical notion of Tasteless, or without flavor, and therefore contrary to Sapido [flavorful], or Saporito [savory], for example: insipid Apples; insipid Liquor; insipid Water, etc.; while indeed Insipiente foolish, as the contrary of Sapiente, always refers to morality. If sometimes Insipido, or its abstract name Insipidezza [inspidity], are, by translation, applied to morality, it does not mean already Insipiente, or Insipience, or Sciocco, or Sciocchezza, as the Crusca surmised, but rather What is lacking in gusto [taste], or moral spirit, for example: insipida [insipid] answer; insipida Story; Insipido amusement, and the like, in which for sure Insipido and the like cannot equal Isciocco.

Insulso [bland] [f. insulsa / pl.m. insulsi - pl.f. insulse], Latin. Insulsus, as composed of negative In, and Latin Sulsus or salsus (Salty, or Salt), literally means What is not salty, or savory; and so it was said in Latin: "olea insulsa amurca rigare" (Colum. 2, 2), and so properly is also said in Italian "They made the plants bigger, and more apples, But of insulso flavor" (Alam. Colt. l, 22). For this reason Insulso differs from Insipido, applied to the physical; because the first alters the quality of the flavor, and the other deprives the subject of every flavor. Insulso, then, elevated to the metaphorical, approaches, the metaphor of Insipido, saying: insulsa Request; Insulso Essay; Insulsa conversation, etc.; but it cannot therefore be said to be a true synonym of Sciocco, as the Crusca asserted under the heading Insulso, in which it did not separate the proper from the metaphorical sense (12).

(12) The Crusca, to express notions equal to those of the additional already explained, introduced in their Vocabulary a large number of Florentine jargon words, that have nothing in common with the national language; and indeed it makes me wonder how Sr. Cherubini has taken the vain care to collect ninety similar words of a similar sordid commodity, to counterpose to his metaphorical slang term Articiocch (Vocab. Ital. Mil.). It seems to me that the real purpose of a Vocabulary of provincial dialect should be to make known the true Italian words that correspond to to the local, and not those of the jargons of other dialects. We certainly will not deal with the explanation of things thus made.

Insano [Insane] [f. insana / pl.m. insani - pl.f. insane], Latin. Insanus, being composed of the negative In, and the adjective Sano, literally means not healthy. Now, as the attribute Sano applies both to the physical and the moral, saying for example: Health of the Body, Health of the mind; so also the opposite Insano should refer as much to the original as to the displaced. But the use ingrained in our language that the lack of physical health is marked with the adjective Malsano [Unhealthy] (See Infermo and Poor health), and Insano is only used to indicate disease of the mind, which is why it is called Insania [insanity], for example: "Atamante became so insane That seeing the lady with two children ... He cried out, Hold the nets" (Dant., Inf. 30); "He showed himself to us a man insane with grief" (Petr., Son. 35). Insano, then, is a generic attribute that denotes the state of one who does not have a healthy mind; and therefore can not be said to be fully synonymous with Stolto and Pazzo: not with Stolto, because this already we applied the notion of little sense: not Pazzo for the reason that we are to expose.

Pazzo [f. pazza / pl.m. pazzi - pl.f. pazze], (13), says the Crusca, is one Who is oppressed (ie, taken) by Pazzia; which is defined the same way: Lack of discourse and of sense; The contrary of Saviezza. But it was needless to say lack of discourse, because where there is no sense there cannot be sustained proper discourse; that if for lack of speech the Crusca intended deprivation of speech, this is supposed disproved by the fact, because the pazzi are, without comparison, the most talkative of the wise [savj]. If Pazzo is therefore the opposite of Savio, the Pazzo will be one who thinks, speaks, works differently and contrary to that which suggests sense, and therefore it is very similar to Stolto, the common notion of a lack of understanding. However, since the actions of the Pazzo are more extravagant, more exaggerated in fantasy, more diffusive than the Stolto, because the lack of understanding in the Pazzo occasions heating or distortion of the imagination, given that the Pazzo differs from the Stolto who cannot make use of hindsight due to weakness of the senses, or inadequate in understanding, as we explained above. I do not make reference to the examples of the Crusca, because they are not suitable for endorsing the notion expressed, which moreover is supported by the common intelligence. I reflect only that when Pazzo is applied, to inanimate subjects, it equals Istrano, and not to Istolto: so what is called Pazzo is what is extravagant; Pazzo (for strange) joke. Pazzia is thus a kind of Insanity.

(13) Ferrari imagined that Pazzo came from Lat. Fatuus; but to this little persuasive origin Muratori (Voc. Pazzo) preferred that of Menagio, who had Pazzo descend from the Latin verb Patior [suffer]: but when I reflect that real pazzi suffer nothing and often their mind is even restrained by pleasant imaginings, I do not think I am induced to adopt such an origin.

Folle [fool][f. folle / pl.m. - pl.f. folli], (14), for the Crusca, is made equivalent to Pazzo, Stolto, Matto, Vano; it seems to me that the closest among those is Vano. In fact the Crusca itself, talking about Folleggiare [foolishness], derived from Folle, defines it as operating without consideration, i.e. Vaneggiare [prattling]. That concept conforms to the accepted meaning, as it is mainly described by Folle, one who, of slight talent, and vanished from view, loses himself in vain thoughts, emits ridiculous speeches, keeps himself in occupations ineptly, and indulges in childish frascherie [foolery], for example: "In vain .... folleggiamenti [foolishnesses[ to spend the time" (Guitt. Lett.). One was led to write all "the follie and scipidezze that are done" (Nov. ant. 74, 1); "Follia does not mix with knowledge" (Dic. div.).

(14) Monosini and Vossius drew the etymology of Folle from that of the Greek word Phaulus; Menagio from Latin Follis (Bellows): but Muratori (Voc. Folle) considering that the German language has the word Faul, meaning man of naught, senseless, languid, etc., and that a similar word, with equal significance, dominates also in French and English, that the Cimbric Fol equals Fatuo insipiente, and that in the end among the ancient Celtic words Ffoll is found, meaning Stolto, was inclined to believe that such a word is of Teutonic origin.

Matto [f. matta / pl.m. matti - pl.f. matte], (15) for the Cruca not defined, nor definable by the examples that it alleged, is equated by them to Pazzo and Stolto; but according to the common notion, however, that the use concedes to such an attribute, it seems to be a mixture of pazzia and follia; since ordinarily Matti are regarded as those who, for some disorder occurred in the organism of their brain, no longer reason, or work any longer with that judgment and wisdom which sane men are wont to use. Mattezza therefore can be related to a more extensive disease of pazzia and follia. However, it is observed that common discourse often adopts the word Matto with the same notion as Pazzo; and in this case the two words can be said to be targeted as of equal value nor will there be a distinction between them if not for the fact that use assigned to Pazzo greater nobility than that of Matto (16).

(15) Matto, for Caninio, Monosini, and Menagio was taken from the greek Mataios, or rom the obsolete Mao. Esychio deduced it from the greek Mattabos (Stolido, Fatuo); but Muratori, who was persuaded to have our language come from languages more northern than Greek, deriving from foreign words, advances the opinion that the the Italian word Matto ihas been taken from the german word Matt, or Matz, meaning Debole [Weak], Balordo [stupid], Insane, etc . (Voc. Matto). In the Lombard dialect the word Matto also refers to physical things, saying: Matto Wine, for spoiled; Matto gold, for false, or of no value, etc. Showing the moral analogy to the Matto, he supposes that such a word belonged to that ancient Italian language, which in these countries was spoken before Latin.

(16) From the radical Matto were taken as synonyms, the names Mattezza, Matteria, Mattia, etc.; but in common usage is preserved only Mattezza, and the others can be taken as antiquated.

Demente [f. demente / pl.m - pl.f. dementi], Latin. Demens, is not explained by the Crusca, but only by them equated to Sciocco and Pazzo. It thus keeps to the track of its value in Latin, from which it was drawn. Latin Demens consists of the prepositional diminutive, or pejorative, De, and Mens (Mind), and literally means injury of mind, or degradation of the intellectual faculties. By this notion the Latins also used the attribute Amens (Ament); although some experts of that language have marked a difference between the one and the other of these two words, since Amens (17), consisting of the prepositional deprivation, and Mens (Mind), means He who is devoid of reason; but when one is considered Demente he is not, in fact, equipped with a whole mind, but still retains some part of the common reason (18). The notion of Demente therefore, according to the equation just now explained, would differ little from Scemo, Stolto, Sciocco; but since the mental imperfections of these attributes are related to natural defects, i.e. dependent on a bad human physical constitution, and so they may differ from that of Demente, believed accidental, and a kind of Insanity.

(17) The Crusca does not welcome into its text the word Ament, although they have received the abstract nuun Amenza, derived from Ament; but if it recorded the cognate words Demente and Demenza, by analogy it could also admit Ament. It cannot then be seen why they declared antiquated the noun Amenza, which would serve to indicate the difference in the text between in Demente and Ament. So it is not to be understood well the reason for which the Crusca, after having stated as current use the verb Dementare (Render demente), has held as antiquated the word Dementato (Made, or Rendered demente), a legitimate participle of the verb.

(18) Forcell., Lex., word Demens.

Montecatto [f. mentecatta / pl.m. mentecatti - pl.f. mentecatte], lat. Mentecaptus, is explained by the Crusca as Infirm of mind. It conforms to the common acceptance, according to which Mentecato relates to Injury of the mind. So, for the explanations already reported, such an attribute can be considered identical to Demente, and not synonymous with Sciocco, or Pazzo, as the Crusca asserted.

Deliro [Delirious], lat. Delirus (19), according to the Crusca under the heading Delirare, is an attribute of the state that is applied to One who is beside himself, who has lost his speech, and who frenetica. Delirio being a kind of Insania, and consequently a disease of the mind, it is a game of strength to resort to the language of doctors to obtain an exact definition. According to them, Delirio is a frequent symptom in inflammatory fevers, blood loss, bites or stings of venomous beasts, in the upset of the diaphragm [of the eye, the iris], etc., because of which the mind is disordered and distorted, so that all becomes inept exercise of ordinary and regular operations. The examples, however, put forward by the Crusca offer us Deliro under the generic notions of Pazzo, Vaneggiante, etc., for example: "Every delirious enterprise" (Petr., Song H. 6, 2); "With such an aspect as mother throws on delirious son" (Dant., Par.1); "Why thus delirious, he said, Thine intellect from what is its wont?” (Dant., Inf. 11). If the Delirio is constant and vehement with great aberration of mind, and accompanied by acute fever, by ravings, by vigils, etc., then the patient is called Frenetico, because his illness by doctors is called Frenitide, or Frenezia [Frenzy], from which Frenetico is derived (20). By the Crusca it is defined by the Evil (disease) of the Frenezia that offends the mind (without adding the cause and manner) leading it to furore and pazzia, for example: "After a desperate frenezia and pazzia, many return to their right mind" (S. Crisost.); "As happens in continuous fever, ending in blood flow, and in frenetichezza (frenzy)" (Booklet. Cur. diseases of). Other examples, however, that the Crusca advance show Frenetico with kindred notions of pazzia, of Delirio, distorted Fantasy, etc. (See Frenetico under the heading Veement). When the Delirio excites ideas or movements of a considerable impetus, without regularity and without order, but accompanied by ardor, by anger, and violent shaking of the body, then the delirio becomes Mania, which, for lack of fever, is distinguished from Frenesia.

From Mania, a Greek word, is formed Maniaco: for example: "Those who suffer from mania are called maniaci [maniacs]" (Lib., cur. malatt.); and Mania was defined by the Crusca with the following example: "Mania is a furore with inclination to strike" (Ibid.). In combining Mania with Furia, it was because in common language Maniaci qualified by Furor: "But seeing him furious rising to beat his wife again" (Bocc., No. 73, 24); "Almost furious he had become ... .he shouted" (Ibid, Nov. 99: 50). Furia [Fury], however, or Furore, though expressing a fit immoderately predominating over reason, not always being produced by natural disease, but mostly by outrage and anger, cannot be said identical to Mania; and consequently the furiosa are not always Maniacs: wherefore it is that to Furioso is applied frequently the notions of Impetuous, Beastly, Pazzo, Insane, etc. (see. Furioso, under the word Veemente).

(19) The word Deliro is composed of the prepositional De, meaning in this case declination, and Lira, which, among the ancients, equaled One pulled in a straight line, so that Delirare was taken in the generic sense of Deviating from the straight; and then figuratively Deliro was taken in the sense of One who deviates from reason. To this notion accords the example: "So much delira, this comes out of the groove, that goes astray" (But., Inf. 11); as well as this: "Delirare, is to get out of the groove of the truth, as the ox out of the furrow, when it impazza [goes crazy] and is not obedient to the yoke" (Ibid., Par. 1, 2).

(20) Not already Farnetico, Farneticamente, Farneticare, Farnetichezza, as the ancients used popularly for idiocy [idiotismo]. Frenetide thus is a Greek word, composed of Phryn (Mind) and Itis (Disease). Doctors thus called Parafrenitide That disease supposedly caused by inflammation of the diaphragm [of the eye, the Iris].

Forsennato [f. forsennata / pl.m. forsennati - pl.f. forsennate], is an attribute composed of Fuori [Out of] and Senno [sense], to indicate an individual who is out of his senses. Such an attribute can indeed be synonymous with Demente, with Mentecatto, and also with Insano; but I do not think it can correspond to the Latin Furibondus, Furens, Furiosus, as the Crusca asserted, since in the attribute Furioso, as we explained, is conceived as of effects not common to simple Forsennato. Examples indeed put forward by the Crusca under the heading Forsennato show only a harmless dementia and lack of reflection, but not already an iruption to the detriment of others, as for example: "Forsennata she barked like a dog" (Dant., Inf. 30); "And more and more matto and forsennato is one who struggles, and thinks he knows his principle" (Nov. ant. 28, 2); in these examples there could be no sure substituting Furioso for Forsennato. And if the Crusca for the noun Forsennataggine opposed the Latin nouns Stultitia, Dementia, it could not be supposed for certain that the primitive Forsennato corresponds to those of Furens, Furibondus, Furiosus.

Notes

1 - Ortensio Lando, Paradossi, cioè sententie fuori del commun parere, novellamente venute in luce (Paradoxes, i.e. sayings out of the common opinion, newly come to light], In Venetia, printed by Andrea Arrivabene, 1563, Paradox V, p. 22. The first edition appeared at Lyons, printed by Giovanni Pullon da Trino, in 1543. See about the essay I Paradossi del Lando (in Italian) by prof. Andrea Vitali.

2 - Writing over the head: Nosce te ipsum (Know yourself). It is cited as an inscription in the forecourt of the temple by Pausanias in Description of Greece 10.24.1, and also by Plato in the Phaedrus, 229e.

In the ears: Auriculas asini quis non habet (Who doesn't have donkey's ears?). Witticism ascribed to Lucius Annaeus Cornutus, a Roman stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD.

Top of the forehead: Ô caput elleboro dignum (O head, worthy of a dose of hellebore). Hellebore, a poisonous plant used medicinally since Antiquity, was reputed to induce madness.

The lower part of the forehead: Hic est mundi punctus et materia gloriae nostrae, hic sedes, hic honores gerimus, hic exercemus imperia, hic opes cupimus, hic tumultuatur humanum genus, hic instauramus bella, etiam civica (This speck of a world is the substance and seat of our glory, here it is that we fill positions of power and covet wealth, and throw mankind into an uproar, and launch wars, even civil ones). Cited from Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia (Natural History), Book 2, Chapter 68.

In the chin: Stultorum infinitus est numerous (The number of fools is infinite), (Vulgate: Ecclesiastes 1:15).

Inside the coat of arms (left side):Democritus Abderites deridebat, Heraclites Ephesius deflebat, Epichthonius Cosmopolitus deformabat (Democritus of Abdera [city of Thrace] deriding (1), Heraclitus of Ephesus [city of Greece] weeping (2), Epichthonius Cosmopolitus deforming). Epichtonius is the Latin word for a kind of insect or cockroach (here united to the fool), whose characteristic, Cosmopolitus points out, is to be found throughout the world. As cockroaches, driven by instinct, deform and ruin things with which they come into contact, so the same intended here for the action of fools.

(1) From the city of Abdera derived the term Abderitism, by which is meant a particular conception of the philosophy of history that understands it as unchanging a senseless agitation of men. The Abderites followed a dissociated pattern of behavior towards the philosopher Democritus, their fellow citizen: they first welcomed him with open arms and later publicly condemned him as insane, because he wanted to impose on young people not to travel - hence the metaphor of immobility in the story - so they would not become intelligent, a condition of absolute inconsistency.

(2) For Heraclitus all those who lived on earth were condemned to remain distant from the truth because of their miserable folly of appeasing the insatiability of the senses and the ambition to power.

Inside the sphere (right side):Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas (Vanity of vanities, all is vanity), Vulgate: Ecclesiastes 1:2.

Inside the medallions on the shoulder: Ô curas hominum, Ô quantum est in rebus inane (Oh, the cares of men; oh, how much emptyness there is in the things), motto of Aulus Persius Flaccus, Satire, I. / Stultus factus est omnis homo (Each man is made foolish) (Vulgate: Jeremiah 10:14) / [Verumtamen] Universa vanitas omnis homo [vivens] (Every man living is an absolute vanity). Vulgate: Psalm 38:6.

3 - Barzelletta Nuova qual tratta del giuoco, dal qual ne viene insuportabili vitii, a chi seguita ditto stile, gionge a increpabil morte (New joke which deals with the game, from which it is insupportable vices, to those who follow the said style, reaching an incredible death), Brescia, Bernardino Misinta, s.d., [c. 1502]. See by Thierry Depaulis the article «Entre farsa et barzelletta: jeux de cartes italiens autour de 1500», The Playing-Card, vol. 37, no. 2, Oct.-Dec. 2008, p. 89-102.

4 - Paolo Antonio Tosi, Commedia e Farse Carnovalesche nei dialetti Astigiano, Milanese e Francese misti con Latino Barbaro composte sul fine del sec. XV da Gio. Giorgio Alione [Comedy and Carnival-style Farces in the Astian, Milanese and French dialects mixed with Barbarous Latin composed at the end of the XVth century by Giorgio Alione], Milano, 1865, p. 368. See the essay Taroch - 1494 by prof. Andrea Vitali

5 - The letter can be found in the book edited by Vittorio Rossi, Lettere di messer Andrea Calmo riprodotte sulle stampe migliori [Letters of Messer Andrea Calmo reproduced in the best prints], with introduction and illustrations by Vittorio Rossi, Torino, Loescher, 1888, pp. 482-483. See the essay Theroco Wind by prof. Andrea Vitali.

6 - The etymology of 'Scirocco' or 'Sirocco' is to be derived, according to the Dizionario Etimologico [Etymological Dictionary] of Ottorino Pianegiani, “dall’arabo SCIOUQ, che tiene a SCIARQ, oriente, onde SIARQUI orientale e anche scirocco. In francese e provenzale: siroc; in Spagnolo: sirocco, jiroque, jaloque, aloque; in portoghese: xaroco. Nome di vento fra Levante e Mezzogiorno: dai Latini detto Noto” ("from the Arabic SCIOUQ, which is SCIARQ, the East, hence SIARQUI, Eastern, and also scirocco. In French and Occitan: siroc, in Spanish: sirocco, jiroque, jaloque, Aloque, in Portuguese: xaroco. Name of wind in the Levante and the Midi: by the Latins called Noto"). The name xaroco in Portuguese seems very interesting, very similar to our taroco, in addition to the Arabic term Sciouq, reminiscent of our sciocco [silly, simple, simpleton]. In short, etymologies that somehow recall in their entirety the meaning of tarocco as sciocco, folle [foolish, crazy].

7- See the essay by professor Andrea Vitali Rochi and Tarochi.

8 - Also on this topic you can read the essay Tharocus Bacchus Est by prof. Andrea Vitali and the first essay of four by Prof. Michael S. Howard, Dionysus and the Historical Tarot I - II - III – IV.

9 - About this topic you can read the essay Treatise on the game of Minchiate by prof. Andrea Vitali.

10 - Flavio Alberto Lollio, Invettiva di F. Alberto Lollio accademico Philareto contra il giuoco del tarocco [Invective of F. Alberto Lollio, Philareto academic, against the game of tarot], ms. 257, cc. 30, 1550, Ferrara, Biblioteca Ariostea. See the essay About the etymology of Tarot by prof. Andrea Vitali.

11 - Cfr: Massimo Zaggia (ed.), Teofilo Folengo. Maccheronee Minori [Minor Maccheronee], Einaudi, Turin, 1987, p. 619. See the essay Taroch: vulgar latin by prof. Andrea Vitali.

12 - See the essay A 'Cavaleyro' taroco by prof. Andrea Vitali.

13 - Carlo Dionisotti, Italia e Mantova [Italy and Mantua], in "Atti della R. Accademia delle Scienze di Torino - Parte Morale" [Acts of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Turin – Moral Part], v. 72, Torino, 1937, p. 14. See the essay Taroch: nulla latina ratione by prof. Andrea Vitali.

14 - Ottorino Pianigiani, Vocabolario Etimologico della Lingua Italiana [Etymological Dictionary of the Italian Language], Word Briscola: we propose two etymologies of which both lead to the idea of beating, hitting. Some from Fr. BRICHE, the name of a certain game done with sticks, then applied to a kind of game done with cards and that seem to be connected with the radical germ. BREC: break, split, whence also Fr. Bricole, briccola, medieval war machine for throwing stones, and also kind of game with balls (see Briccola); others prefer a derivation, at least in the sense of Knock, from Middle High German. BRITZE, mod.PRITSCHEN: strike. A confirmation of the etymology is that in familiar language Briscole means also Smash, Knock,, and that one of the four suits of Italian cards is represented by sticks and that the Ace and the Three, which are the highest, are called the Carichi, loads, almost representing in relation to the others a group of wood pieces or sticks. - Kind of game that is played with the cards by two or four persons: so-called perhaps because each of the players tries to hit or take the opponent's card. Deriv: briscolàre = beat, strike.

About the etymology of Poker, the following derivations can be considered: from the French poqué (fool) or from the English poke, slang term in America, Australia and South Africa meaning 'pockets or wallets' and by extension the loose change that is usually carried inside. And also from the German Pochspiel, name of a card game similar to poker, from pochen, "to brag as a bluff", literally "to knock, rap".

15 - Cesare Ripa, Iconologia [Iconology], In Roma, Printed by Lepido Faeij, 1603, p. 381. See the iconological essay The Fool by prof. Andrea Vitali

16- See the essay Folly and 'Melancholia' by prof. Andrea Vitali.

17 - Dance song by Girolamo Benivieni, 1453-1542. See the iconological essay The Fool by prof. Andrea Vitali

18 - Roberto Personio, Guida degli Uomini alla loro Eterna Salute, Cap. IV: Contra l’amore del Mondo [Robert Persons, Guide of Men on their Eternal Health, Chapter IV: Against love of the World], Roma, Komarek, 1737, p. 413. The author was a Jesuit. See the essay Folly and 'Melancholia' by prof. Andrea Vitali.

19 - Eugenio Garin (ed.), Erasmo da Rotterdam: Elogio della Follia [Erasmus of Rotterdam: Praise of Folly], Milano, Mondadori, p. 116.

20 - Tutti i Trionfi, Carri, Mascherate o Canti Carnascialeschi andati per Firenze dal tempo del Magnifico Lorenzo de’ Medici fino all’anno 1559 [All the Triumphs, Chariots, Masquerade or Carnival Songs of Florence from the time of Lorenzo the Magnificent de' Medici up to the year 1559], Ex Museo Fiorentino, 1750, Part I, pp. 159-162. This song was later performed for many voices in Florence at Carnival in 1546, when it staged a wagon of madmen [pazzi] which presented several categories of people, especially the lame and deformed. Among these was Jeronimo Amelonghi, called the Hunchback of Pisa, mocked by Alfonso I de' Pazzi in the following verses:

A Jerónimo Amelonghi

O Gobbo Ladro, spirito bizzarro,

Che dì tu or di me? hai tu veduto,

Che i Pazzi come te vanno sul Carro,

Ed io, che Pazzo son sempre vissuto,

E morrò Pazzo, al trionfo de' Pazzi

Non son per Pazzo stato conosciuto?

To Jerónimo Amelonghi

O Hunchback Thief, bizarre spirit,

Is it you or me? have you seen,

How Madmen like you go on the Wagon,

And I, who have always lived Pazzo [Crazy],

And will die Pazzo, at the Triumph of Madmen [de' Pazzi],

Was not recognized as being Pazzo?

(Reported in the Sonetti d’Alfonso de’ Pazzi contro Benedetto Varchi, con diversi Madrigali, e Strambotti del medesimo [Sonnets of Alfonso de’ Pazzi against Benedict Varchi, with several madrigals and strambotti by the same], in “Il Terzo Libro dell‘Opere Burlesche” [The Third Book of burlesque Works], In Usecht al Reno [i.e. Roma], Jacopo Brofdelet, 1771, p. 348).

21 - Michelagnolo Buonarruoti the Younger, La Fiera, commedia e la Tancia, commedia rusticale [The Fair, comedy, and Tancia, rustic comedy], with annotations by Abbot Anton Maria Salvini, Firenze, Tartini e Franchi, 1726, p. 40.

22 - Volume Secondo [Second Volume], Milano, Giovanni Silvestri, 1825, pp. 91-99.