Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, June 2014

Ippolito d'Este (Ferrara, 1479-1520), fourth son of Duke Ercole, from childhood had been invested with high prelature dignities. At only five years of age he had become commendatory of the Abbey of Canalnuovo, at seven, Archbishop of Strigonia in Hungary, Cardinal at fourteen and at seventeen Archbishop of Milan. Later he was Archbishop of Narbonne, Modena, Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica, Abbot of St. Mary of Pomposa, of Fellonica, of S. Faustino and holder of many other benefices. The example of the many offices combined in one person and the transfer of high dignity to a child, although common in his time, caused great scandal to his contemporaries. He grew ambitious, cruel, vindictive, always eager to excel and loving to excel in entertainments and luxury, including, of course, in games.

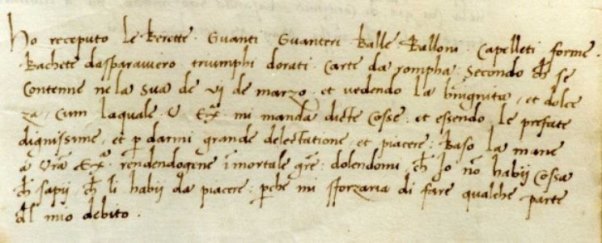

On May 2, 1492, while he was in Hungary, he wrote to his mother, Eleanor of Aragon, a letter in which he thanked her for having received from her, among other things, a deck of golden triumphs:

“Ho receputo le berette, guanti, guanteri, balle, balloni, capelleti, forme, bachete da sparaviero, triumphi dorati, carte da rompha, seconda che se contenne ne la sua de VI de marzo, et vedendo la benignita et dolceza cum la quale vostra exzellenza mi manda dicte cosse et essendo le prefate dignissime et per darmi grande delectatione et piacere, baso la mane a vostra excellenza rendendogene immortale grazie, dolendomi che io non habii che sapii che li habii da piacere, perche mi sforzaria di fare qualche parte del mio debito". (I received the caps, gloves, cases for gloves, small balls, balloons [or large balls], hats, frames, rods for hawks, golden Triumphs, Rompha cards, in the amount that your (chest) could include on 6 March, and seeing the kindness and the sweetness with which your Excellency sent me these things and being for the aforementioned highly commendable and giving me great delight and pleasure, I kiss the hand of Your Excellency wishing her immortal thanks, regretting that I do not know what would please her, because I would strive to do anything to repay her) (1).

To drive away boredom during long winter evenings and trips by barge through the Po Valley canals in the sunny days of summer, he played Vaca and Taroco (2) and Triche Trache with his closest companions, who had the names of Pontigino dalle Sale, Geronimo da Sestola, Camillo Costabili, Bigo Compagno and the Jew Abraham, nicknamed Tubesec (3).

Ippolito lost much more than he won - especially with the buffone [professional buffoon] Girolamo (or Geronimo) da Sestola, called Coglia (4) - as evidenced by the meticulous records of his secretary (5). On October 10, 1506, for example, Ippolito lost large sums of money on his way by boat to Forli to visit Pope Julius II (6).

He had a disagreement with Ariosto to whom he apparently addressed, regarding Orlando Furioso, the question, "Where did you find, Messer Ludovico, so much nonsense?" A fact that led people of the time to think he was an ignoramus, although in reality he is to be counted, among princes and cardinals, one of the most learned of his time (7).

Of Don Antonio de Guevara, Spanish writer (Treceño, Asturias di Santillana, c. 1480 - Mondoñedo, Lugo, 1545), Franciscan inquisitor of Toledo and Valencia, Bishop of Cadiz and Mondoñedo, we wrote (1539) in another essay (See Triumphs, Trionfini Trionfetti), in reference to his work Menosprecio de corte y alabanza de aldea. We still remember his Libro llamado Relox de príncipes (1529), better known by the title Libro aureo del emperador Marco Aurelio (Golden Book of Emperor Marcus Aurelius), in practice a guide to princes, and the Epístolas familiares (1539), a work that had numerous translations in French and English, and had a great influence on euphuism (8).

Below is a passage from Epístolas familiares in the Italian version translated by Domingo de Gatzelu (9), almost a contemporary of de Guevara, who was not only a translator, but also royal Spanish secretary and knight of the Order of Malta. The piece relates to one of the many privileges that de Guevara believes should be reserved to the old men, that is to play triumph and tarot after lunch, recommending that the gaming tables never lack fresh fruit and wine:

Libro Secondo - Privilegio 24

Privilegio de vecchi è passar tempo doppo mangiare et giuocar alle carte al triompho over ai tarocchi over alle tavole in casa de vicini potendo andarvi, et non potendo, mandarli a chiamare. et il caso è che hora il vecchio giuochi largo hora curto, sempre mai bisogna che sopra la tavola vi siano delle frutte et del miglior vino che nella terra si trovi"....Di Valenza alli XII di Febraio MDXXIII.

Second Book - Privilege 24

“The Privilege of old men is to spend the time after eating in playing cards, triumphs or tarot, or at boad games, in the homes of their neighbors if they can go there, and if not being able, sending someone to call on them, and in all cases, whether old men play a lot or a little, there always needs to be fruit on the table, and the best wine in the territory”. .. In Valenza 12th of February 1524.

In Como’s Biblioteca Comunale [City Library] are kept some burlesque verses, or humorous and satirical vulgar poems, in manuscript form without indications of the authors. For a long time it was assumed that they were by the hand of Paolo Giovio the Elder, but a careful analysis found them deriving from other writers. Vittorio Cian, who was able to study those manuscripts in depth, writes about them: "The pages seem to be written by two different hands, mostly by a person of Como contemporary with Paolo Giovio, a relative or friend of his, perhaps his nephew Alessandro or Giulio Giovio, or more probably Luigi Raimondi; others by Paolo the Elder himself. Certain internal and chronological reasons, more than graphological ones, seem to me sufficiently serious to make it unlikely that the poems of the first group belong to Paolo Giovio the Elder. I will mention only a few. First of all, these chapters, mostly burlesque, should be attributed to the youth of the historical Como personage (who was born in 1483); but, as in them are clear allusions to Berni, of whom they are a blatant imitation, their composition must be referred to a period of about three decades earlier" (10).

And it is precisely the poetry reminiscent of Francesco Berni (11) that attracts our attention. It is a satire directed by its author to Luigi or Giovan Luigi Raimondi, a poet of Como and a relative of Giovio, who, for his eccentricities and passion for burlesque poetry, called himself the Necromancer and Berna (from Berni). Vittorio Cian hypothesizes that it was Raimondi himself who composed the text, as a burlesque autobiography (12).

The author begins by writing that he had played cards until seven in the morning:

Come sapete voi, signor, hersera 1

Stei fin alle sette hore a andar a letto

Ch’io giocai fin all’hora alla Primiera

As you know, sir, last night

I stayed up until seven before going to bed

Since I played Primero until then.

and that he had then gone to bed without sleeping. Getting up, he writes that he began composing verses on Luigi Raimondi, held by him in high consideration:

E volendo ch’io dica il mio parere

Dirovvi che costui, più che non pare 35

È avveduto, e huomo da vedere.

And if someone wants me to say my opinion

I will say that he, more than he might seem,

Is circumspect, and a man to know.

At this point the author begins to wonder why his friend wanted him to be referred to as Berna [a name very close to “Berni”], given that his reputation preceded him even without that nickname:

Egli è un huom singular alla moderna,

E acciò con gli altri egli non si confondi

Fassi da tutti nominar il Bema 60

He is a singular man and modern,

And so that he will not be confused with others

He has himself called Berna by all.

Che ci son molti luigi Raymondi

Com'el si chiama in vero, e a questo nome

Non credo ch'el giovanni soprabondi.

It 's true that there are many named Luigi Raimondi

As he is called, and to this name

I do not think that there abound [those who are also called] Giovanni.

Se costui si trovasse in mille Rome,

Fra mille genti, saria conosciuto, 65

Et senza anchor nomar il suo cognome,

If he were in thousands of Romes,

Among thousands of people, he would be known,

And without even giving his surname.

Tal che se mai l'incontro e lo saluto,

Hora Diego, hora Berna, lo dimando,

Hor Negr.[omante], hor huomo resoluto.

So if you ever met and greeted him,

I would call him now Diego, now Berna,

Now Necromancer, now resolute man.

Onde m'accorgo s'io gli vo pensando, 70

Ch'egli ha più nomi assai che m.[esser] Carlo,

Over che non ha il nostro honorando.

So I realize, if I think of him,

That he has names more numerous than Messer Carlo,

Or rather, that he has a different way than ours of being greeted.

Era in dubbio talhor come chiamarlo,

Perciò ch'io temea seco di fallire,

Che in tutto io voleva contentarlo. 75

Sometimes I was in doubt about what to call him,

So I was afraid of making a mistake with him,

Because I wanted to please him in everything.

Io non sapea talhora come dire,

Per li nomi di questo huomo da niente,

Ch'essendo tanti mi facea stuppire.

Sometimes I did not know what to call him,

Because of the names of this man of nothing, (1)

There being so many astonished me.

(1) Of nothing = because he doesn’t called himself by his real name, the author defines him as a man ‘of nothing', in the sense that he kept his true origin Hidden.

In short, anyone would have grieved him if he had not been called as he wished.

Ma adesso ho conosciuto chiaramente,

Che sol il Berna dir se gli bisogna, 80

Perchè l'amazza chi dice altramente,

But now I have clearly understood,

You need only call him Berna,

Because he is heartbroken by those who call him differently.

The last lines express the considerations of the author, who believes that for him not to be called Berna meant for the friend to underestimate him.

Non so pensar perchè non si vergogna

D'esser cos'ì chiamato questo alocco

S'egli d'esser il Berna non s'insegna.

I cannot understand why he is not ashamed

To be called in that way, this dunce.

If he does not call himself Berna himself.

Venga il cancar al goffo, et al Tarocco, 85

Pensa imitar il Berna, in fé da dovero,

Guardate s'egli è nato in tutto sciocco.

May cancer come to Goffo (1), and to the game of Tarocco (2),

He really thinks to imitate Berni,

Make yourself aware of how he was born absolutely foolish

So ch'egli a poca cosa non s'appiglia

A metter in tai cose il suo pensiero,

Questo m'accresce pur gran meraviglia, 90

I understand that he does not occupy himself

With things of little importance,

This thing makes me wonder a lot.

Che se gli dichi il Berna, e per ragione:

Costui al Berna in niente s'assomiglia.

I non so da che venga la cagione

If he is called Berna, you need to think,

This person resembles Berna in nothing

I don’t understand the reason

Di questo nome, salvo se 'l imita

Nell'essere mai sempre arcipoltrone. 95

For this name, except that he mimics him

In never being an arch-idler.

(1) Goffo or goffetto was a variant of Primero (For more information on this variant, see the article La Primiera di Francesco Berni (The Primero of Francesco Berni) at the site www.tretre.it edited by Girolamo Zorli, a partner of Associazione Le Tarot).

(2) The line Venga il cancar al goffo, et al Tarocco (May cancer come to Goffo and to Tarot) is a curse directed at the two games Primero and Tarot, on which Berni had written, resulting in his friend's desire to imitate him, because of the love they shared for those cards.

The following notes to the text were compiled by Vittorio Cian during his examination of the composition (13):

“vv. 61-3. By this it seems to me that the author is saying that his friend's name was Giovan Luigi Raimondi.

v. 76. At first the author had written, and then deleted,: Per la confusion de' nomi (Because of the confusion of names).

v. 79. Between this line and the following one, is written, then deleted: Questo Tarocco certo se l’insogna / D'esser il Berna (For sure this Tarocco dreams / Of being Berna).

Here we are confronted with further evidence of the meaning attributed to the word “tarocco” in the XVIth century, of fool, simpleton.

Gabriel Chiabrera (Savona, 1552-1638) was celebrated as an Arcadian poet and playwright. of the purest tradition; he composed several odes including the Anacreonice and Pindaric, in addition to sermons, sacred and profane lyric-epic poems like La disfida di Golia, Il leone di David, La conversione di Santa Maria Maddalena, Alcina prigioniera, Erminia, Le Perle (The Challenge of Goliath, The Lion of David , The Conversion of Saint Mary Magdalene, Alcina prisoner, Erminia, The Pearls), narratives, didactic essays like Delle stelle, Il presagio dei giorni, Le meteore (About the Stars, The Omen of the days, The Meteors), heroic poems like Delle guerre de' Goti, 1582; Amedeide, 1620 (About the wars of the Goths, 1582 Amedeide, 1620), tragedies, dramas, dramatic and sylvan actions. Il Rapimento di Cefalo (The abduction of Cephalus, with music by Giulio Caccini, performed in Florence in 1600 for the wedding of Marie de’ Medici and Henry IV), an autobiography and several dialogues. His verses were much appreciated by the musicians of the time (Monteverdi, Caccini, etc.) who set them to music. The most famous, among many, was the song Belle rose porporine (Beautiful crimson roses).

His Letters (about five hundred) were published posthumously several times. What is meant by 'Letter' is explained by the Editor of the Letters of Chiabrera in the edition of our reference (1762) (14) "According to ancient tradition, [the letter consists] in a trade of feelings and discourses between two absent ones, so that they know their presence with their mutual correspondence".

In one of these letters (c. 1620) addressed to a Genoese friend, Chiabrera mentions a decree that had banned the games of Tarot and Ganellini (Ganellini was the name of Minchiate in Liguria and Sicily. See in this regard the essay Ganellini seu Gallerini), a decree that would have angered not only a certain Lady Emilia, who, by other letters, we know as a passionate player (Letters 28 and 81). In fact, in Letter 28, while the author wishes health to his friend, Chiabrera wishes to the aforesaid Lady "good fortune in Gannellino"!

Lettera 29

"La lettera di V. S. emmi venuta oggi, perciò rispondo tardi. Piacemi ch'ella stia bene fuori di carnovale, e la ringrazio dell'invito, et io non l’harei appettato, se il tempo tuttavia non fusse perverso. Ma io non posso far prova di me, tanto il verno orrido mi ha battuto. Come 1'aria si faccia tepida la prima Galea mi porterà a V. S., e l’animo mio è di dimorare costì tutto il tempo caldo, et alla maniera delle serpi lasciare la vecchia spoglia dentro coteste care loggie. Ho in quest'ozio dato quell'ordine, che ho potuto, alle mie Poesie; a quelle cioè, ch'io delibero di stampare: moltissimi fogli da me chiamati solazzi, holli ordinati similmente, ma non ho già animo di stamparli: consegnerolli ad alcuno, che dopo me ne faccia sua volontà. In tal modo mi fono allontanato dalle Muse, e starommi muto, ovvero passerò la noia con alcun Sermonetto. Intanto V. S. scriva alcuna volta. Mi si dice, che sia fatto decreto, e che siano proibite le carte per Tarocchi, e per Gannellini, perciocchè fra loro sono alcune figure di Angeli, e Cieli, e simili: non so come l’udirà la Signora Emilia, a cui &c....Savona".

Letter 29

“Your Ladyship's letter arrived today, so I reply late. I am glad you are well over the time of the Carnival, and I thank her for the invitation, and I would not have waited, however, if the weather were not so perverse. But I cannot put myself to the test considering that the horrible winter has hit me. As soon as the air is warm, the first ship will take me to Your Ladyship, and my mind is with you all the warm weather and in the manner of snakes, leaves the old forms in these dear lodges. During this leisure, I have put in order, as I could, my Poems; those I think of printing: I likewise set in order many sheets which I call 'Solazzi', (Solaces) but still haven’t the desire to print: I will give them to someone who, after I am dead, will do what he wants with them. So I have moved away from the Muses, and I'll be mute, or pass the boredom with some ‘Sermonetto’ (small Discourse). Meanwhile Your Ladyship writes me sometimes. I was told that a decreet was made that Tarot and Gannellini cards are forbidden, because among them there are some figures of Angels, and Heavens, and the like: I do not know what Signora Emilia will think about it etc…… Savona” (15).

The Jesuit Giacomo Filippo Porrata, editor of the book, expresses himself about this Decree thusly: “Tarocchi &. Tal era, ed è la delicatezza del Governo Serenissimo nell’invigilare su tutto ciò, che può dar sospetto di pregiudicare, benché leggiermente la Pietà, e la Religione” (“Tarot & Such. So was and currently is the sensitivity of the Most Serene Government in watching over everything that can give suspicion of prejudicing, however slightly, Piety and Religion" (16). The expression 'however slightly' (benché leggiermente) indicates that the monk did not consider, however, it such a great crime to play those two card games.

Cesare Rinaldi (1559-1636), who had great fame in his time, took part, although young, in various Academies of Bologna. Appreciated by Marini, to whom he directed his letter (reproduced in the First Book of his Letters), he had severe critics against him, as evidenced by Crescimbeni, who in his Commentarj intorno all' Istoria &c. (Commentaries on History etc. - Vol. 5. p. 160) writes: "Romulo Paradisi gives a critical judgment on the style of Rinaldi regarding his use of vicious and preposterous metaphors, as he claims to have seen in a copy of the Considerazioni del Tassoni sopra il Petrarca (Tassoni’s considerations upon Petrarch), annotated by Paradisi himself in his own hand .... where Tassoni marveled of certain modern writers who spent their time calling the swelled sea Idropico (Dropsy), the woods moved by the wind Paralitici (Paralytic), the grass gnawed by the cold Etica (Ethical), and the like" (17). A lover of painting, he befriended the most famous artists of the time, and in particular Caracci, Guido Reni, Fontana, Faccini, Valesio and others. From him were published the Madrigali (Madrigals-1588), the Rime (Verses -1590) and the Canzoniere (Song Book-1601), in addition to the Lettere (Letters - 1617) that he sent to famous personages of the time (18).

In one of his letters to an anonymous recipient, he talks about his favorite game, of course Tarot, that saw him almost always losing, considering it exceedingly more 'monstrous' to lose because of bad luck than not to write a friend for fear of bothering him, promising instead because of this, to continue to write him and never play again, so as not to be bullied by adverse fate:

“Al Signor...

TRABUCCAI per troppo yoler esser cauto, che imaginandomi V.S. aggravata da continue occupationi non hò voluto da un tempo in quà faticarla nella lettura di mie lettere, ond'ella, tutta sdegnosa, mi rinfaccia il silentio, e n’incolpa il giuoco, come s’egli in me fosse vitio e non ricreatione. Io giuoco à Tarocco; giuoco da me favorito, ma non à me favorevole, in cui non seppi mai, che fosse guadagno, e stimo cosa più mostruosa il perder sempre per mala sorte, che il restar per modestia di scriver ad un amico, attorniato da mille affari, ma non tacerò più, perch'ella meco più non s'adiri, né giuocherò mai più, per non vedermi di continuo tiranneggiato dalla Fortuna. Di Bologna il di ultimo di Decembre 1613".

“ To Signor……….

I put a foot wrong by wanting to be too cautious, because imagining Your Lordship aggravated by continuous occupations, I did not want to tire you with the bit of time reading my letters, so that you, all indignant, accused me for my silence, and blames the game, as if it was for me a vice and not a recreation. I play Tarot, my favorite game, but not favorable to me, in which I never knew what was the gain, and I consider it more monstrous to lose due to bad luck than not writing, out of modesty, to a friend surrounded by thousands of business affairs, but I will not keep silent any more, so that you will not be angry with me any longer, nor will I ever play, so as not to see me constantly tyrannized by Fortune. Bologna, the last day of December 1613".

Giovan Battista Marino was born in Naples October 14, 1569, and died in the same city March 26, 1625. Considered one of the greatest representatives of Italian baroque poetry, he created a widely diffused style with the name of Marinism. His poems, exacerbating the artifices of Mannerism, is centered on intensive use of metaphors, and the antitheses of all the games of phonic correspondences, from those relative to apparent etymology, to the showy descriptions and the delicate musicality of his verse. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the fortunes of Marino declined because his works were considered a symbol of bad baroque taste. His writings were revalued during the XXth century (he was much admired by Benedetto Croce), following the resurgence of interest in analogical processes in poetry.

To his friend upon the entry of an Ambassador

This is a somewhat comical letter intended to make known to his friend the unspeakable ugliness of the entry of an ambassador into the city. The only thing of note was, according to Marino, "a sky, laughing with a temperate air, and sunshine so wonderful, that for God it was a day worthy of one of those ancient Triumphs of Caesar". On the contrary "The pomp was very impoverished by the unwise actions, standing between disgrace, indecency, and disorder, that always intervened in such festivities: that day it appeared in such a way that you saw nothing but a large mass of beasts that resembled an smashed army".

One thing, however, was too funny: a Master of Pages who, striding high up on a dried up mule with "legs beyond measure, similar to the Giraffe" and with a really hilarious arsenal of garments and ornaments. This man was a "really big fat man of fifty, with a grim face in the murky light, with cropped beard, and large staring eyes, who seemed like Philip Melanchthon" [in attitude and physical expression: Melanchthon was a collaborator of Martin Luther].

After this illustration, the author proceeds to describe his clothes, the bridle and the mule’s saddle, in addition to everything else that made his person ridiculous. In a nutshell, a character worthy of taking part in the most crazy of carnivals. This is one of the author's many comments: "He wore a long loose coat in the shape of a Cope, made half with tooled leather and the other half with felt, with sleeves to the elbow, embellished grotesquely with iron wire, such that neither Giotto nor Cimabue ever invented a more horrified mosaic of flaps and folds. In addition, hanging on one side was a bronze inkwell of enormous size, and on the other a Breviary with buckles made of musket parts, wrapped in a shiny cowhide Flemish bag, enough to put fear into any cheeky Devil. I leave you to judge the rest; even yet I laugh, and I do not think that India, in the unloading of its Fleet, ever sent into our world a more monstrous animal than this" (19).

If we have dwelt on this description, it is to comment on the final lines of the letter: “Immaginatevi se per far un'appendice alle Carte di Tarocco, si può trovare la più bella figura” (Imagine, as an appendix to the Cards of the Tarot, being able to find the best figure) which means that although the figurative elements present in each of the tarot cards were many and sometimes really extravagant, none of these would have been able to compete with the complexity of the figure of that great hulk.

The seventeenth-century historian Fedele Onofri in his Sommario Historico (Historical Summary), in the chapter on "Who was the first who began to navigate, who first had Lordship over the Sea, who discovered the compass, and who was the inventor of many other things" writes that “I Greci trovorno i Tarocchi” ("The Greeks found the Tarot")(20), which is to say that the tarot were invented by the Greeks. An assignment which is not surprising given that the origin of chess and playing cards came from many sources and for many centuries were traced to Palamedes, a mythological Greek hero, to spend the time between one fight and another under the walls of Troy.

Giuseppe Ippolito Pozzi (Bologna 1697 - about 1752), was a humorous poet, physician and lecturer in anatomy. He left the 4th canto of the collective poem [poem with many authors] Bertoldo, Bertoldino and Cacasenno (1736) and the Rime piacevoli (Pleasant Verses), published posthumously in 1764. This is the presentation he gives of himself in the volume of his Verses (21):

Sonnet 1

Portrait of the author

Son lungo, e magro; son franco, ed ardito,

Ed ho due anni più di trentasei;

Sono di membra in proporzion guernito,

Nè più bel, nè più brutto esser vorrei.

I am tall and slender; I am frank and bold,

And I am two years older than thirty-six;

I am of members in proportion granted,

Neither more beautiful nor uglier would I be.

Non ho ricchezze, e pur non son fallito;

Ho due Figli, e fra due mesi sei;

Di tre Mogli a quest' ora io fui Marito,

Volete altro saper dei fatti miei?

I do not have riches, yet I am not a failure;

I have two children, and in two months six;

Of three Wives at this time I was Husband,

Do you want to know more of me?

Amo de' Scacchi, e de' Tarocchi il Giuoco;

Son iracondo, e frettoloso a un tratto ,

E fra Medici, e Vati ho qualche loco.

I love Chess, and the Game of Tarot;

I am angry and anxious at once,

And among Doctors and Poets have some place.

Mi convien far da savio, e pur son matto,

Mangio ben, bevo meglio, e studio poco:

Quest' è la vita mia, quest'è il Ritratto.

I ought to act as a wise man, yet I am mad,

I eat well, drink better, and study a little:

This is my life, this is the portrait.

From the Opere del Conte Algarotti (Works of Count Algarotti), i. e. Francesco Algarotti, 1712-1764 (whom we have discussed in the essay I Tarocchini nel Settecento, currently in Italian only), we quote a short passage from a letter sent by a friend in Bologna April 12, 1741. The reason for the letter is to respond to questions from Count Algarotti, desirous of knowing from his friends which, among the poets in the vernacular, should be taken as an example for his “aggiunti ed epiteti” ("additions and epithets"). After mentioning Petrarch, Dante, Chiabrera, Frugoni, Tasso and Casa, the friend passes to salutations that direct the Count also to several friends, recalling besides a certain Gabrielli he knew to be in correspondence with the Count, emphasizing with the following words the fact he hadn’t changed at all: : “Egli è quale egli era: giuoca continuamente a tarocchi perde e cospetta” ("He is what he was: he plays tarot, continually loses, and is surprised") (22). One of many examples where, once again, is evidenced the great attraction that the game of Tarot had in all social classes.

Giancarlo Passeroni (1713-1803), of whom we have written in the essay I Tarocchini nel Settecento, in his Rime [Verses] s mentions the tarot several times. He directs a ferocious satire to Lorenzo Luzi, Academician of Florence, for the unbearable fact of being constantly forced to defend himself against his critics, openly manifested in public assemblies. The torment was similar to that caused to him by flies that the poet really could not stand: he could tolerate the discomfort caused by mosquitoes and fleas, to say nothing of mice, as well as a great number of animals, but never so irritating and unbearable to Luzi as the obsessivity of the fly. To highlight the consequences of the bites of flies in his eyes, the poet resorts to the seventeenth triumph, that is, the Moon, meaning that he would have seen the darkness, the night and with it the moon, even before the sun went down: Me gli caccian talvolta anche negli occhi; / E mi fanno veder, pria dell’occaso / Del sole, il diciassette de’ tarocchi" (They sometimes even get into the eyes; / And make me see, before the sunset, the seventeenth of the tarot".

Non è animal nel mondo, ch’io conosca,

Che m’abbia dato, o dia maggior molestia

Di quella, che ogni dì mi dà la mosca.

There is no animal in the world I know

That has given me, or gives me, greater harassment

Than that the fly gives me each day.

Solo a udirla ronzar mi vien la bile;

Ogni stanza mi rende aspra, e molesta;

E fia per quanto vuol, vaga e gentile.

Only to hear it humming raises my bile;

Every room makes me bitter and troublesome;

However meandering and polite it wants to be.

Le fiere chiuse stan nelle foreste;

Se a cercar non le andiamo a bella posta,

Non ci vengon a rompere la testa.

The fairs are closed in the forests;

If we try not to go to them on purpose,

They don’t come to us to break our heads.

La pulce fa con noi continue danze;

Ci punzecchia talor; ma poi non viene

A imbrattarci la mensa, e le pietanze.

The flea makes continuous dances with us;

It teases us sometimes; but then doesn’t come

To soil the table and dishes

Talor ci rode il topo la giornea,

Ci mangia il cacio, è ver; ma non vien mica

A disturbarci in pubblica assemblea.

Sometimes the mouse gnaws in the day with us,

He eats the cheese, it is true; but then does not comes

to disturb us in the public assembly.

Ci assordano la state le cicale,

A guisa de’ Poeti; ma nel resto,

Ch’io sappia, non ci fan né ben, né male.

Cicadas deafen us in the summer,

As if they were Poets; but for the rest,

To my knowledge, they do to us neither good nor bad.

Ci punge lo scorpione; e grave, e infesto

E ‘l suo veleno, il ciel ne scampi i cani,

Ma non facci altro mal fuori che questo.

The scorpion stings us; and severely, and infesting

Is his poison, heaven save the dogs,

But does nothing worse than this.

Ci pungono le vespe, e i tafani;

Ma con un po’ di zolfo, e un po’ di paglia

Facilmente si tengono lontani.

Wasps and horseflies sting us;

But with a little sulfur, and a little straw

Easily are kept away.

Ci danno qualche noia le zanzare;

Ma basta andare in luoghi di buon aria,

Che non se ne vede una, o almen son rare.

Mosquitoes give us some trouble;

But just go to places with good air,

You never see one, or at least they are rare.

Piace il dolce alle mosche; io lo so bene;

E trovando il mio sangue di lor gusto,

Mi penetran sì addentro nelle vene.

Flies like sweets, I know well;

And finding my blood to their taste,

They penetrate me so into my veins.

Mi caccian nelle gambe in mia malora,

E nelle mani i lor pungenti stocchi,

Che traggon dalle vene il sangue fuora.

They get into my legs. to my misfortune,

And in my hands their prickly rapiers

Draw out the blood from my veins.

Me gli caccian talvolta anche negli occhi;

E mi fanno veder, pria dell’occaso

Del sole, il diciassette de’ tarocchi.

They sometimes even get into the eyes;

And make me see, before the sunset,

The seventeenth of the tarot.

.

Per porle in fuga io m’ affatico invano;

Se battute da me cangian pur loco,

Vi so dir, che non van troppo lontano.

To put them to flight I labor in vain;

If beaten by me they indeed change their place,

I can tell you, they do not go too far.

Si scostano da me, ma sol per poco:

Scacciate appena tornano ben presto

Al lor primo lavor, al primo gioco.

They remove themselves from me, but only briefly:

Once expelled they come back quickly

To their first job, to the first game.

Io credo, che mai più sarò contento,

Pensando pur, che un animal sì vile

Debba essere la mia noia, il mio tormento.

Luzi mai più, che già mi vien la bile.

I believe that I'll never be happy,

Thinking about the fact that so cowardly an animal

Should be my annoyance, my torment.

No more, you already give me an attack of bile (23).

A second poem is dedicated to Signor Pietro Crippa, a friend of the poet. Here he speaks of hunting and on the need not to live it as a pleasure in killing animals, but rather as an opportunity to breathe fresh air, watch the hills, rivers, meadows and trees for the sheer pleasure of the view. Here Passeroni embodies the ideal of the true hunter: to shoot a little and enjoy nature. Exactly the opposite of what his friend liked. Choosing the theme of the hunt. to meet the tastes of his friend, the poet begins a brief description of what is in opposition to it in a series of situations that certainly do not reflect the pleasures of his friend

Chapter 1

Going hunting….

E’ ben altro che, stando accanto al foco,

Arrostirvi le gambe, ed i ginocchi,

Altro che tempo perdere nel gioco.

It is indeed something else, standing next to the fire,

Roasting the legs and the knees,

Other than losing time in the game.

Al gioco di tresette, o de’ tarocchi,

O alla bassetta, ove pensose, e mute

Stansi le genti, e parlan sol cogli occhi.

At the game of Tresette, or of Tarot

Or of Bassetta, where people are thoughtful,

And mute, and talk only with their eyes.

Ben altro che ‘l parlar della virtude,

Oppur del vizio, o di guerra, o di pace,

O logorar sui libri la salute.

Indeed something other than talking of virtue,

Or of vice, or of war, or of peace,

Or wearing out one’s health on one’s books (24).

The third poem is a sonnet on the most beautiful game, that in which you win, and the on undeniable truth that always gets lost. But the poet does not give up even in the most difficult moments, willing to gamble everything, even his teeth, or rather a tooth that hurts, even if he believes that, with the bad luck that accompanied him, the dentist was going to take, in addition to the tooth, also the jaw.

Sonnet

Il più bel gioco, a mio parer, è quello,

In cui si vince: il vìncer piace a tutti,

E dolci son della vittoria i frutti,

Vincasi pur la cappa, od il mantello.

The most beautiful game, in my opinion, is the one

where you can win: everyone likes to win

And sweet are the fruits of victory,

You also win the cowl, or the mantle.

Per questo nessun gioco a me par bello,

Anzi mi paion tutti quanti brutti;

E credo, che tra noi gli abbia introdutti

Calcabrina, Astarotte, o Farfarello.

For this reason no game seems good to me,

In fact they all seem to me so ugly;

And I think that among us they have brought

Calcabrina, Astaroth, or Farfarello. (1)

Di giochi io sonne più di sette, e d' otto;

Gioco a tre sette, all'ombre, ed a tarocchi,

A bazzica, a primiera, all'oca, al lotto.

Of games I know more than seven or eigh;t;

I play Tresette, Ombre, and aTarot,

Bazzica, Primiera, Goose, the lottery.

Ma o sia, che la fortuna mel' accocchi,

O sia che forse io non son troppo dotto,

A ciascun gioco io perdo i miei baiocchi.

But whether fortune disadvantage me

Or that maybe I'm not too learned,

At every game I lose my pennies.

Basta ch' i dadi io tocchi,

Oppur le carte, io son più, che sicuro

Di perdere, e nel gioco io più m'induro.

It’s enough for me to touch the dice,

Or the cards, and I'm more than certain

To lose, and in playing I more inflict myself

Di riscattar proccuro

Quel, che ho perduto, e sempre va crescendo

La perdita, ed ancora io non m' arrendo.

With worry to get back

what I have lost and always grows more

The loss, and yet I don’t hobr up.

E vo fra me dicendo:

Si cangerà la sorte, perch' è varia,

Ed ogni dì la provo più contraria.

And I'm saying to myself:

My luck will change, because it is varied,

And every day I feel more guilty.

Ella giammai non varia ,

E si mostra ostinata a' danni miei,

Più che non son nel loro error gli Ebrei.

It never changes,

And shows itself obstinate in my damage,

More than the Jews in their error

Qualche baiocco avrei,

Se in vece di giocar, facessi versi,

Che non avrei perduto quel, ch' io persi.

I would have some pennies,

If instead of playing, I did verses,

I would not have lost, what I lost.

Giacchè mi son sì avversi

Tutti i giochi, vorrei, che fra le genti

S' usasse almeno di giocare i denti

Che senza complimenti,

O per dir meglio, senza far parole,

Uno ne giocherei, ch' assai mi duole.

Since all games are so adverse to me

I would wish that among people

teeth were used for gambling

So that without compliments,

Or to say it better, without words,

I would gamble one that much pains me.

Se alcun giocar lo vuole,

Io nol ricuso, purchè a proprie spese

Cavar mel faccia il vincitor cortese.

If anyone wants to play for it,

I shall not deprecate him, provided at his own expense

The courteous victor removes it from me.

Ma dopo tante offese

La fortuna sarebbe, che 'l Barbiere,

O 'l dentista, che sa meglio il mestiere,

Con mio gran dispiacere

Mi caverebbe coll' adunco ferro

I denti buoni, e bei, che in bocca io serro.

But after so many offenses

My luck would be that the Barber,

Or the dentist, who knows the job better,

To my great regret

Would remove with the hooked iron

The good and beautiful teeth that I grit in my mouth.

Quel solo, se non erro,

Che mi dà gran molestia, ed è tarlato,

Per mostra mi saria da lui lasciato.

E son sì fortunato,

Che credo, che con mia crudele ambascia,

Mi strapperebbe il dente, e la ganascia.

Only the one, if I'm not mistaken,

That gives me great trouble, and is worm-eaten,

for all to see would he leave to me.

And I'm so lucky,

That I believe that with my cruel anguish,

He would tear out the tooth, and the jaw (25).

(1) These are the names of three devils

Notes

1 - Modena, Archivio di Stato, Casa e Stato, Carteggio estense, busta. 135 (Modena, State Archive, House and State, Este Correspondence, envelope 135). This letter was discovered by Giulio Bertoni in Poesie, leggende, costumanze del medio evo (Poems, legends, customs of the Middle Ages), Modena, 1917, p. 218. See also: Le Carte di Corte. I Tarocchi. Gioco e Magia alla Corte degli Estensi (The Cards of the Court. Tarot. Game and Magic at the Este Court), edited by G. Berti and A. Vitali, Ferrara, 1987, p. 17.

2 - A Ludus Vaccarum is mentioned by Pietro Sella in his Nomi Latini di Giuochi negli Statuti Italiani (sec. XIII - XVI) (Latin Names of Games in Italian Statutes - XIIIth – XVIth centuries) in reference to a statute of Feltre dated to XVIth century (IV-60), one with a Ludus Vachettae in Padua in the XIIIth century (785), and one in Rovereto in 1425, "Ludum taxillorum, vel andruzorum, vachetae" (42). The list of games of Pietro Sella appears in his Glossario Latino Emiliano, Glossario Latino Italiano, Stato della Chiesa-Veneto-Abruzzi (Latin Emilian Glossary, Latin Italian Glossary, State of the Church-Veneto-Abruzzi), XIX, 419, Vol. 109 of Studi e Testi Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Apostolic Vatican Library Studies and Texts), 1944, pp. 199-214.

3 - Tubesec = you be goat. Giving extravagant and obscene nicknames was a frequent habit imposed on many of those on familiar terms with the Estensi.. Abraham 'Tubesec' was also an assiduous gambling companion of Duke Alfonso.

4 - Girolamo da Sestola is known to scholars for his famous letter of 7 July 1533, from which is deduced a definite date of Ariosto’s death. Master of dance and music, horseback riding, a skilled fencer, skilled trinzante (carver), messenger of trust and custodian of the jealous secrets of state, Coglia was not a court jester, but as others like him, such as Moschino and Barone, willingly took on the mask of the clown to make themselves more pleasing to their lords. He was in the service of Ippolito, Alfonso I and Ercole II, living at the court of Ferrara for more than half a century (1490-1545). See: Michele Catalano, Messer Moschino. Beoni e buffoni ai tempi di Ludovico Ariosto (Messer Moschino. Drunkards and fools in the time of Ludovico Ariosto), in “Giornale Storico della Letteratura Italiana" (Historical Journal of Italian Literature", Vol. 88, Turin, Giovanni Chiantore 1926, p. 34.

5 - See concerning the long list reference, c. 2 of the register of 1507.

6 - Debtors and Creditors, 1506, c.6v.

7 - Cfr: Il cardinale Ippolito e la sua corte (Cardinal Ippolito and his court) in Michele Catalano, “Vita di Ludovico Ariosto: ricostruita su nuovi documenti” (Life of Ludovico Ariosto: reconstructed from new documents (Vol. I, Firenze, L. S. Olschki, 1930, pp. 179-183.

8 - Euphuism is a rhetorical device which consists of alleviating the harshness of a concept by replacing the word with a paraphrase or another word that is felt to be less raw.

9 - Libro Secondo delle Lettere dell'Ill. s. don Antonio di Gueuara, vescovo di Modognetto ... tradotte dal s. Dominico di Catzelu (Second Book of the Letters of the Illustrious don Antonio di Guevara, Bishop of Modognetto, translated bys. Dominico di Catzelu), Venezia, Gabriel Giolito De Ferrari, 1546, p. 227.

10 - Vittorio Cian, Gioviana. Di Paolo Giovio poeta, tra poeti e di alcune rime sconosciute del sec. XVI, (Giovana. Di Paolo Giovio poet among poets, some unknown verses of the XVIth century) in “Giornale Storico della Letteratura Italiana” (Historical Journal of Italian Literature", Vol. 17, Torino, Ermanno Loescher, 1891, p. 305.

11 - To know the text of Berni on the tarot see the essay Tarot in Literature I

12 - Vittorio Cian, Gioviana, op. cit, p. 314.

13 - Ibid. p. 316.

14 - Giacomo Filippo Porrata, Lettere di Gabriello Chiabrera (Letters of Gabriello Chiabrera), Bologna, Lelio dalla Volpe, 1762, p. IV.

15 - Ibid., pp. 23-24

16 - Ibid., p. 145.

17 - Giovanni Fantuzzi, Notizie degli Scrittori Bolognesi (Informaiton on Bolognese Writers), Vol. VII, Bologna, S. Tommaso d’Aquino Press, 1789, pp. 187-189.

18 - Lettere di Cesare Rinaldi, Il Neghittoso Academico Spensierato, [dedicate] all’Illustrissimo et Reverendiss. Sig. il Signor Cardinal d’Este (Letters of Cesare Rinaldi, the Neglectful Carefree Academician, [dedicated] to the very Illustrious and Most Reverend Signor Cardinal d'Este), Venezia, Tomaso Baglioni, 1617, p. 143.

19 - Lettere del Cavalier Marino (Letters of Cavalier Marino), in “L’Adone, Poema del Cavalier Marino. Con gli Argomenti del Conte Fortuniano Sanvitale e l’Allegorie di Don Lorenzo Scoto. Aggiuntovi la Tavola delle Cose Notabili, Con le Lettere del medesimo Cavaliere” (The Adonis, Poem by Cavalier Marino. With discussions byCount Fortunato Sanvitale and Allegories by Don Lorenzo Scoto. Adding the Table of Notable Things, with the letters of the same Cavalier), Second Volume, In Amsterdam, 1680, pp. 32-34 of the Letters (Part Three).

20 – Our edition of reference: Fedele Onofri, Sommario Historico. Nel quale brevemente si discorre delle sei Età del Mondo (Historical Summary in which briefly is discussed the Six Ages of the World), Venezia, Antonio Remondini, undated, p. 142.

21 - Our edition of reference: Rime Piacevoli del Signor Giuseppe D' Ippolito Pozzi, (Pleasant Verses of Signor Giuseppe D' Ippolito Pozzi), London, Domenico Pompeiati, 1790, p. 3.

22 - Opere del Conte Algarotti (Works of Conte Algarotti),Vol. XI, Letter XVIII, Carlo Palese, 1794, p. 210.

23 - Giancarlo Passeroni, Rime (Verses) Tome I, Milano, Antonio Agnelli, 1775, pp. 79-87.

24 - Ibid, pp. 199-200.

25 - Ibid, pp. 415-416.