Translation revised by Michael S. Howard, Feb. 2012

We continue in this article with the themes developed in the essay About the Etymology of the word Tarot, based on our new considerations. The occasion has also allowed us to make a digression on the relationship between Chess and Tarot in social, symbolic and philosophical terms (1). Regarding the origin of the Tarot word, see also the essays Taroch: nulla Latina ratione, Tarot: vulgar Latin, Taroch-1494 and, in particular, Tharocus Bacchus Est.

A further hypothesis concerning the etymology of the word Tarot is that the term may result from a popular expression related to towers, whether intended in the general sense of fortifications or in reference to the chess piece. In fact there are similarities between chess and tarot not only due to the presence of some common figures (King, Queen, Knight, Pawn, Rook): while both were considered intellectual games, their educational content was nevertheless emphasized. While we know that the order of tarot cards in some way reflected the Mystic Staircase, chess represented well the different classes of society (2), as described by the Dominican Jacobus de Cessolis (1250-1322) in the work Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium super ludo scacchorum(c. 1300), for which the "recreational game of chess contains instructions on morals and battles of human generation" (3).

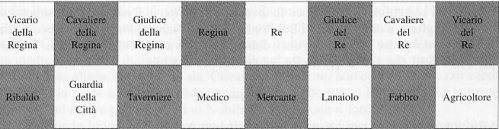

Cessolis's work is based on the pictorial representation of the main pieces as referring to real people who held the same position in the life of the time: Rex (King), Regina (Queen), Arfiles o Arphiles (Bishops, King's and Queen’s judges) (4), Milites (King and Queen’s Knights) and Rochi (such as Vicars of the King and the Queen), while the Populares (Pawns) are combined with one or more specific categories of workers: agricola (rural), faber (artisan, blacksmith), notarius (secretary), lanificus (wool worker), carnifex (executioner) scriptor (scribe), mercator (merchant), medicus (doctor), tabernarius (host), tabularius (notary, cashier, accountant), hospes (hotelier), custor civitatis (city official), ribaldus (villain), cursor (messenger), lusor (player). The chess board represents the city itself, which is that of Babylon, where the Dominican believed the game had been invented. This attribution allows the author to explain what the tasks of each person were in the social structure and the honorable modes of behavior which all had to embrace.

The city of Babylon with the arrangement of the various characters, by Jacopo de Cessolis

Cessolis’s work was an inspiration for other treatises on the subject, like the one written by Meister Ingold which, in his Guldin Spil dated 1423 in a background of eschatological anxiety, provides the following scheme, reflecting a spiritual hierarchy:

King = Jesus Christ

Queen =Mary

Bishops = patriarchs and prophets

Knights = martyrs

Rooks = twelve apostles

Pawns = men of the earth

Ingold concludes his work with the following words: "The chess board is Time, with white squares for the light of the day and black squares for the night. When time is swept away by death the game ends and no one has an advantage. No one is King or Knight or Judge or Lord: everyone is equal in the bag of the Earth".

Continuing the discussion about chess, it should be remembered that the chessboard itself was understood as a symbol of the earth due to its square shape right from its creation, where a great battle between good and evil took place and where the game had the function of teaching the values of wisdom, temperance and shrewdness. "The penchant for symbolism, the figure and the allegory finds its natural expression in the configurations of the game. Every aspect is an opportunity to establish a parallel with the organization of human life and everything is brought back to the customs and beliefs of the time. The Middle Ages perceives every form of cunning and the traps of the devil behind every configuration: so if the dots on the dice are emblems of Christianity - God = one, two = heaven and earth, three = Trinity and so on - then everything is a clever invention of Satan using the symbols of religion to draw the believer toward gambling and therefore perdition. The religious morals of course do the lion's share and use the pieces and their scenarios to warn and educate people to Christian ethics. Common examples are repeated from the first interpretations. Among the oldest is a manuscript attributed to Pope Innocent III, but more likely to be ascribed to an English author of the thirteenth century, entitled Quaedam moralitas de scaccario. There are some subjects that were to have a long literary life, from the works of morality to those of Cervantes. First of all you establish an analogy between the world and the chessboard, of which the colors, black and white, show the two conditions of life and death, of praise and blame following the prayer or sin. Another highly successful subject of course is the vanity of earthly things. Like people, the chess pieces have different values, honor and fortune, but the return to their common origin eliminates any differences and often in the bag (the earth) that collects them at the end of the game, the king lies beneath all the others" (5).

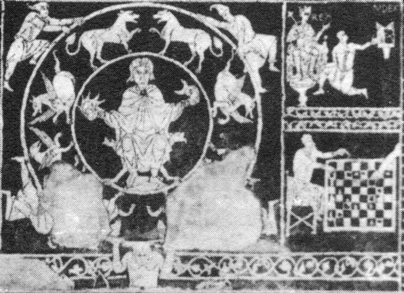

It is not by chance that in the Church of St. Savino at Piacenza a 12th century mosaic floor depicts two men playing chess next to a large Wheel of Fortune. A teaching on Vanitas (vanity) was well stated by the Ludus Triumphorum which had the educational purpose of conveying the values of Christian ethics and ways to lead a life of virtue (6). A journey that involved a dualistic contrast between spirit and matter, between activity and passivity, between reason and irrationality (7).

Chess players

Floor mosaic, XII century. Crypt, St. Savino Church, Piacenza.

Wheel of Fortune

Floor mosaic, XII century. Crypt, St. Savino Church, Piacenza.

Wheel of Fortune, Chess game, King with a Judge (1)

Mosaic floor, XII century. Crypt, St. Savino Church, Piacenza

(1) In the band on the right side, above the chess players, a king (indicated by the word REX) is seated on a throne, accompanied by a judge (IUDEX) who points to an open book where the word LEX appears.

Many coats of arms depict towers and chessboards for the purpose of conveying the ideas of strength, endurance and pugnacity in a conflict in which the need to overcome the opposition is felt.

Coat of arms of Cairo Montenotte (Savona)

Leaving aside the philosophical content underpinning the game, we to return to its purely recreational aspect. In chess, the opponent is called "the opponent" and sometimes even "the enemy" (8). The game of tarot, like chess but using cards, is also a battle in which the object is to vanquish opponents.

Castles (or rooks=“rocche” in the Italian language) were very common in the Middle Ages and could be seen everywhere at that time, emblems of the power of great families that in popular sentiments aroused a strong sense of envy. Since they were considered symbols of social elevation and power, the conquest of a castle was commonly seen as a great demonstration of strength. For this reason, a tower on fire was inserted in tarot cards to represent the Sphaera Ignis, a circle of fire believed to exist above the earth and through which the divinity expressed his great power of destruction (9) and also in chess as an expression of the strength to be overcome. Cessolis, who used the term Roccus (or rook in English) (10) and plural Rochi, identifies this element of chess with the Vicars or the Legates of the King (vicarii seu legati regis) (11). Two hundred years after Cessolis, the term Rochi (with its variant Rocchi) is still in use. Citolini in his treatise Tipocosmia, wrote about chess: ".... the game of chess is a gentleman's game, except that it is a such a great thief of time. Here you will see the chessboard, with its squares and chess pieces such as the King, the Queen, the bishop, knights, rooks, pawns, and how to play chess, to check, checkmate, to draw, to gamble in the game, to hit your companion on the head with the board" (12). The same description in the Piazza Universale (Universal Plaza)by Garzoni (Venice, 1555), Sermon LXIX "De giocatori in universale & in particolare” (About players in general [universale] and in particular) where the author, writing on that game, puts it in this way: "... And at last chess, where you use the King and the Queen, the Bishops, towers, horses, and pawns, with so many games in a row, with so many checkmates on that board, that in the end it is sometimes used to put on your companion's head while you play”. Typical end of a tavern game.

A strategic defensive move called castling (Arrocco) involves the King and Rook (13), term derived from the transitive verb “arroccare” (go to a castling) and in expanded form to mean "to shelter". In the Corsiniano Codex, where the figure of the King is described, castling is introduced thus: "The first piece is called King because as the king is above the people, so this piece is more than all the others; the King, therefore, resides in the most protected position, in the middle of the board, moving one square at a time, both straight and diagonally, to represent the gravity that Kings hold, but just once in the game they can jump three or four squares according to the custom of the country. This jump means that at the beginning of the battle the King retreats to a position where he can’t be attacked, placing his guards closely around for his safety, and throwing the other pieces and pages, which are the pawns, against the enemy’s army to fight for the hoped for victory" (14).The rules of this move did not originate with the invention of the game but were established with time, as Fernando Beretta, historian of the game of chess, writes in his short treatise (15).

Very important for the origin and the development of this move is a discussion by Diego D'Elia, in our opinion one of the highest authorities on the subject, kindly supplied to us and which is given below:

"The most remote origins of this combined movement of King and Tower (Rocco, according to the typical medieval diction) are traceable, conceptually, to the Codex El Escorial (El Escorial Monastery Library) T.I.6, dated to the XIII Century, and the Liber de Moribus ... by Jacopo da Cessole, dated to the second half of the XIII Century: these two texts speak of the jump of the King in different ways, a primitive movement from which, likely, castling is derived.

"The first explicit mention of castling known to me appears in Lucena: Repetición de Amores y arte de axedrez con CL juegos de partidos (Salamanca, Leonardus Hutz and Sanz Lupus, 1497), at f. 38r. Since Lucena takes in and puts in writing what he saw during a live game in Spain, and in the same way, in Italy and in France, we can indicate the historical period of interest in the XV Century. Notwithstanding this fact, at the time identified as a terminus post quem for dating - prudence, in these cases, it is always a must - for this move, however, it should be considered that Giovanni Boccaccio, in Filocolo, wrote about one of the chess games mentioned in the text, a "leap of his rocco", although the movement that Boccaccio - probably - meant was that of the King, and not a castling as we know it today (on this, cf. Adriano Chicco, L’Aiutomatto di Messer Boccaccio, in "Scacchi!", VII (1977), pages 177-178); but it’s very interesting, in my opinion, the terminology used, which I do not think is random, but signifying a tendency in the evolution of this move.

"Again, see the interesting article by Adriano Chicco, Il rebus di Leonardo da Vinci, in "Scacchi!", IX (1978), pages 57-58, where in fact the genius da Vinci used the verb arroccare (to castle) for his invention of a rebus, a place characterized by Chicco as an “extraordinary lexical anticipation”. At this moment, we do not know when or if Leonardo ever played chess, or if the castling move was in use, at least in the places where he lived, or, finally, if he himself played a role in the evolution of this move (even though Leonardo probably did have knowledge of this game), but the use of this term in that historical period remains emblematic.

"For completeness, finally, remember that castling, which had, in the course of its history, different methods of execution, will be mentioned in the by now "technical" texts on the game of chess, including treatises by Ruy Lopez and Pietro Carrera etc., extending to almost epigraphic pronouncements made on it - but now we are in the second half of the XVIII Century - Dominico Ponziani in Il giuoco incomparabile degli scacchi, Modena, Heirs of Bartolomeo Soliani, Ducal Printers, 1769, pages 8-9".

From the way D'Elia writes, it appears more likely that a close relationship can exist between the two games, because the castling move comes, roughly, in the period in which the game of Tarot was developed and characterized.

The castling move is already well codified in 1507. Marco Girolamo Vida (1480-1566), bishop and writer, describes it in his poem Scacchia Ludus (16), known as Scaccheide in its translation into Italian verse (17), when, speaking of the piece of the King, indicates his movements and privileges of him:

Scacchia Ludus

Non illi studium feriendi, aut arma ciendi:

Se tegere est satis, atque instantia fata cavere.

Haud tamen obtulerit se quisquam impune propinquum

Obvius, ex omni nam summum parte nocendi

Jus habet. Ille quidem haud procurrere longius ausit:

Sed postquam auspiciis primis progressus ab aula

Mutavit sedes proprias, non amplius uno

Ulterius fas ire gradu, seu vulneret hostem,

Seu vim tela ferant nullam, atque innoxius erret.

Scaccheide

Li Re non han di offendere desio,

Contenti sol che dagli ostili attacchi

Possan sfuggire, e in sicurtà riporsi:

Nessun però della nemica schiera

Appressarsi osi a lor, che il sommo dritto

Hanno essi di ferir da ciascun lato.

Nè avvanzar più d' un passo ad ogni mossa

A loro lice, tranne il caso in cui

Voglian mutar con un degli Elefanti

La propria sede, mentre allor trascorre

Il Re tanto di spazio in un sol moto

Quanto ve n'ha tra l'Elefante, e lui.

Ma questo cambio è sol permesso quando

Nessun di lor mosso si sia dal luogo

Che ha preso al primo mettersi in battaglia.

Nè frammezzo s'incontri altro Guerriero,

Che il libero passaggio all' Elefante

Tolga, ed al Re, né questi già si trovi

Ai colpi esposto dei Nemici, o giunga

Ad offender col cambio alcun di loro.

(The Kings have no desire to offend, just happy to escape the hostile attacks, in secure repose: but no enemy ranks dare to approach them because they have the supreme right to hurt on every side. Neither of them is allowed to advance more than one square for every move, except if they want to exchange their square with one of the Elephants, in which case the King with only one move travels as much space as exists between him and the Elephant. But this change is only allowed when neither of the two pieces has moved from their square at the beginning of the battle. Nor is there between them another Warrior, which prevents free passage to the Elephant and the King, and the latter does not find himself in any way exposed to the blows of enemies or with this move offending any of them).

Vida, who considers chess a "Fiera immagine di guerre, e finte battaglie / che assomigliano alle vere" (Fair image of wars and false battles / which look like true) recalls the "leap of the King" in another verse:

Scacchia Ludus

Tum cautus fuscae regnator gentis ab aula

Subduxit sese media, penitusque repostis

Castrorum latebris extrema in fauce recondit,

Et peditum cuneis stipantibus abditus haesit.

Scaccheide

Allor prudente

Della fosca Legione il Regnatore (1)

Abbandonò della sua schiera il mezzo,

E chiamando al suo posto l'Elefante (2)

Nelle latebre più remote ascoso

Si tenne del suo campo, e intorno intorno

Si fè di combattenti ampia corona.

(Then the King of the Black Legion prudently left the central place of his ranks and calling the Elephant in his place, hid in the most remote place of his field and around him there was a wide circle of fighters).

(1) Regnatore = The King

(2) Elefante = Elephant, that is, the Rook. Vida describes this piece in the version derived from India, a typology still found in various chess productions: an elephant with a tower placed on its back: "Nec deest quae ferat armatas in praelia turres / Bellua. Utrinque Indos credas spectare Elephantes" (The Indian elephants, which on their back / carry towers full of armed soldiers). In another passage he describes it as follows:

Scacchia Ludus

Tum geminae velut extremis in cornibus arces

Hinc atque hinc altis stant propugnacula muris,

Quas dorso immanes gestant in bella Elephanti.

Schaccheide

Pari a due forti

Ben murate castella gli Elefanti

Serrano i lati delle due falangi

Colle alte torri che sul loro immane

Tergo stan ritte.

(Equal to two strong well-walled castles, the Elephants close the sides of the two phalanxes, hill-tall towers that on their huge backs upright stand).

For Vida the Rook is one of the most important and necessary, pieces. In the explanation in verse of the moves of all the chess pieces, he writes about the Rook thus:

Sed gemini claudunt aciem qui hinc inde Elephanti,

Cum turres in bella gerunt, ac praelia miscent,

Recta fronte valent dextra, laevaque retroque

Ferre aditum contra, campumque impune per omnem

Proruere, ac totis passim dare funera castris.

Scaccheide

Ma gli Elefanti che chiudon nel mezzo

L’intiero campo, allor che le lor Torri

Portano in guerra, e mischiansi in battaglia

Innanzi, indietro, a destra, ed a sinistra

Girano in retta linea, e di funesta

Morte coprono il campo.

(But the Elephants who close into the middle the entire field, when they bear their towers in war and mix themselves in the battle, move in a straight line in front, back, right and left and with fatal death cover the field).

Their loss results a immense damage, as revealed in this passage:

Scacchia Ludus

At niger emicat ense

Stricto eques, et magnis Elephantem intercipit ausis,

Damnum ingens; neque enim est saevae post virginis arma

Bellantum numero ex omni magis utilis alter

Scaccheide

Allor scagliossi il Bruno Cavaliero

Col nudo acciar sul misero Elefante

Che privo di soccorsi, e di difesa

Uopo è che lasci il campo, e vinto ceda.

Il danno è immenso della sua caduta,

Poichè dopo la Vergine, guerriera (1)

Combattente più utile non avvi.

(1) Vergine = The Queen

(Then the Brown Knight lashes out with bare steel against the poor Elephant that with no rescue and defense must leave the field and cede victory. The damage from his fall is immense, because after the Virgin, there is no more useful fighting warrior than he).

Rocchi, together with the other chess pieces, were not immune from being used in verse even in love poems, as we find in Scachier è diventato lo mio core (My heart has become a chessboard), and Tu giochi a scacco Amore (You play chess with Love), two villanelles of the XVI century where the chessboard becomes the field of the love battle between lover and beloved (18).

All social classes played chess, but our examination is concerned with the players of the lower classes, those who played in the taverns. If we bear in mind that in the taverns the game of chess was the companion, along with dice, of tarot, it is not unlikely that at some point - the end of the 15th century - in naming the card game players used an expression that meant attacking opponents, or borrowed a phrase used in regard to rooks or, more generally, the assault of the towers, symbols of power that people wanted eagerly to knock down, an assault with cards to overwhelm the rival, as if with that move the opponent was forced to “arroccarsi” (to entrench himself), or go on the defensive. In fact, the towers were the last bastions in which Lords took refuge to escape from great dangers. Many castles were placed on the tops of mountains (in the Italian language = torre arroccata) not only for the purpose of affording a good field of view but to gain protection against easy conquests. In the Italian language "ti arrocchi” is in fact an expression that one address to someone who has taken such a position. In chess literature, the advice regarding castling is expressed with the terms "s'arrochi" or "s’arrocchi" (19). For the moment, while waiting for the desired results from our research (20), we can only guess some of these expressions, such as “t'arocco, t'arocho, ti arocco, ti arocho, ti rocco, ti rocho” (21) to mean "forcing you to entrench yourself" or "I attack you, I assault you".

To add to the article already quoted, a communication by Giuseppe Crimi, assistant professor of Italian Literature at the Faculty of Humanities, Roma Tre University, comes to confirm our thesis. In a sonnet by Orcagna (22), addressed to Niccolò degli Albizzi, entitled Vorrei che nella camera il Frate (I would like that in the Monk's room), in verse 17 we find the expression "ti do rocco" (I force you to entrench yourself), one of those we mentioned above.

CLXVII

Vorrei che nella camera del Frate

fussimo un dì colle coltella in mano;

se non griderrò tanto a Nepozano,

che le porte d’Arezzo sien serrate;

Quanti dì, quante notti son passate

pure aspettando, ed io aspetto invano,

hommi arrecato pur la penna in mano

scrivendo a te quarantaduo cartate.

Di quei Pisan, che paghâr la gabella

quando gli entroron dentro a quella chiusa,

non ti si fa per or cotal novella.

Ma fa che tu di ciò, non sia medusa,

anzi fa che si meni la mascella

nel modo proprio, qual costassù s’usa:

Ser Bernardo che chiosa,

chi in questa scritta fia Nicola sciocco

a cui l’Orgagna dice: «ti do rocco».

It is therefore a popular expression that would have been widespread among players, to replace the term Ludus Triumphorum with that of Tarocco in its variants Tarroco, Tarocho and Taroch, as confirmed in Renaissance documents that deal with that game. Almost eighty years after the invention of Ludus Triumphorum, of which the ethical and mystical contents were known only to persons of culture, it seems only natural that the game, which enjoyed great popularity in taverns, would have taken a name given to it by its players and chosen from the idioms used in tavern games (23).

This would explain how those who were occupied in the sixteenth century with the etymology of this game did not know its origin, since these people were far removed from the world of the tavern players (24); writers such as Flavio Alberto Lollio and Francesco Berni, or jurists like Andrea Alciati and Pierre Gregoire, or in any case people of culture, like the anonymous author of the Discorso, perché fosse trovato il Giuoco, e particolarmente quello del Tarocco (Discourse on why games, and Tarot in particular, were invented), and religious figures like Francesco Piscina (25). In fact, if Tarot was the name that came out of the cultured environments (almost all social classes played with these cards) its origin would have been known.

Whether the origin of this etymology derives from the vulgar or barbarian term Tarochus or Taroch, which means idiot or fool, game of no value (in which case the hand of the Church cannot be ruled out), or from Bacchus, God of madness (26), or from an expression derived from the frequenters of taverns, so as to become public domain to be acquired by the courts and bourgeoisie, it is certain that the encyclopedic and ethical contents of the game that the term Ludus Triumphorum well represented, had been entirely forgotten. Only a few men of culture continued to wonder about the deeper meaning of those cards, each arriving at completely different answers from the next.

Notes

1 -A remarkable survey by Lothar Teikemeier on the relationship between tarot cards and chess pieces can be found at link http://tarotforum.net/showthread.php?t=161451

2 - Even in a deck of cards painted for Charles VI by French painter Jacquemin (some say to cheer the Prince from his melancholy), we find a personification of the social structure of the time: there were in fact King and Queen, Knights and Pages, to represent the Nobility; the suit cards of Hearts represented the people of the Church; those of Spades, the military; Clubs, farmers; and Diamonds the artisans.

3 - Volgarizzamento del Libro de' Costumi e degli Uffizi de' Nobili sopra il Giuoco degli Scacchi di Jacobus de Cessolis. Tratto nuovamente da un Codice Magliabechiano (Translation into the vernacular of the Book of the Customs of Men and the Duties of Nobles or the Book of Chess by Jacobus de Cessolis. Retranslated from the Codex Magliabechiano), Milan, 1829, Prologue, page 1.

4 - In Cod. Vat. Lat. 1042 Bishops are called Arphyles; in Pal. Lat. 961 Alphinos; in Cod. Vat. Lat. 1960 Assessores with variant ascessores (Iuxta regem et reginam situantur arphili, quasi assessores et iudices). Cfr: Diego D'Elia, op. cit., page 21.

5 - Roberto Carretta, Lo scenario conquistato. Gli scacchi e l’origine del loro simbolismo (The conquered scenario. Chess and the origins of its symbolism), Turin, 2001, pages 48-49.

6 - In this regard, see, at The History of Tarot article, the paragraph on The Celestial Harmony.

7 - About this aspect see the iconological essay The Fool.

8 - cfr: Diego D'Elia, Il Codice Vaticano Boncompagni N.3. Il più complesso e importante Codice Scacchistico della Biblioteca Apostolica vaticana (The Boncompagni Codex Vaticanus N.3. The most complex and important codex on chess in the Vatican Apostolic Library), Trieste, 2000. Chapter One, page 21.

9 - On this subject, see the iconological essay The Tower. In the first order of the Triumphs the card of Strength may have been close to that of the Tower.

10 - In the Italian language it has the meaning of stone or rock, more or less pointed: "E proseguendo la solinga via / Tra le schegge, e tra rocchi dello scoglio, / Lo piè senza la man non si spedìa" (And following the solitary path / Among the rocks and ridges of the crag, / the foot without the hand sped not at all). Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Hell, Canto XXVI, vv. 16-19.

11 - In Codex Vaticanus N. 3, op. cit. Here, the friar’s writing is entitled Tractatus de Ludo Scacchorum Auctore F. Jacobo de Cesolis Ordinis Praedicatorum. In the vernacular translation mentioned above, Book of the Customs of Men and the Duties of Nobles or the Book of Chess by Jacobus de Cessolis, op. cit., the rooks are called Rocchi "In the form of castles these are the vicars of the King", Chapter Five, page 48.

12 - Alessandro Citolini, Tipocosmia, Venice, 1561, page 484. The expression "gran rubbatore" (great thief) of time, here attributed to the game is appropriate to the name of Ludus Latruncolorum given to chess in Roman times surviving in some treatises on the game until the Renaissance.

13 - G. Devoto - G.C. Oli, Dizionario della Lingua Italiana (Dictionary of Italian Language), 1990. Today castling consists of a combined movement of King and Rook subject to the following rules: the King is moved sideways two squares from its place of origin and the Rook is moved to the opposite side of the King. Castling can be done only once. To castle is necessary that the two pieces have never been moved before, that the squares that the King and the Rook move through are empty and that neither the King nor the two squares which the King crosses nor that where it stops is under check. Information on castling can be found in the major Renaissance treatises, such as those by Gioacchino Greco where, alongside special castling methods, there are also those based on current rules. See: Diego D'Elia, op. cit., pages 277-288.

14 - In the Codex Corsiniano 36 E 21, ff. 6v-7r. The manuscript dating back to 1620, a copy by an amanuensis [scribe] of a treatise by Gioachino Greco, is located at the Library of the Accademia dei Lincei in Rome. The original treatise by Greco is kept at the Minutoli-Tegrimi Library (Codex No. 4) in Vorno in the province of Lucca.

15 – "Castling is not an ancient rule. It is clear that this modern and complex movement of pieces was not invented in a day, but was gradually developed from century to century, with the evolution of the rules of the game. In the Indian Chaturanga (what is believed to be the forerunner of chess) no traces of this movement can be found, nor are they encountered in the Arabic Shatranj. The first unusual or exceptional movements made by the King, from which castling evolved, were found in Europe in medieval chess which originated as a modification of Shatranj, to give greater mobility to pieces. A reliable source on the historical evolution of these initial moves is the work of the Lombard monk Jacobus Cessolis, where the rules governing movements of individual pieces were described. In this book it is stated that the king, the queen and pawns have the right to make a first move of two squares in addition to the normal movement. Of these early changes, the double-step opening of the Pawn has survived to our day; in the case of the Queen it became obsolete when it was given its current movement during the great reform of the game at the end of the fifteenth century; whereas for the King there have been many changes before reaching the current form of castling. There is plentiful documentation on the king's moves besides the work of Cessolis, even if the conditions that govern them change. The most common is a move in which the king moves like a knight but with the limitation of not being able to go beyond the second rank. A movement of this type made its appearance in Italy, with a simultaneous movement of the rook resembling the current castling move. The custom of moving the king like a knight disappeared with the rules allowing the king to move from E1 to H1 or G1, and rook from H1 to H1 or E1. This type of "free castling" or "Italian castling" was used in Italy until the nineteenth century, when it was decided to use rules introduced in France during the eighteenth century, which are now the current ones". Fernando Beretta, Breve storia dell'Arrocco (A Brief History of Castling), 2008. Complete overview article at: http://iduepedoni.altervista.org/TuttoIlRestoNotizie.php?fn_page=2&fn_incl=5

16 - The work attracted the attention of Pope Leo X to its author; this pope was a great lover of chess, who, around 1510, wanted Cessolis at the papal court. The success of the poem was huge, with about three hundred published editions, both in Latin and in most important European languages. "The events narrated are in a mythological context. Jupiter and the other gods participate in the wedding feast at the marriage of Ocean and Earth. Ocean himself presents to the guests a chessboard with its pieces, explaining to bystanders the rules of the game, then inviting Apollo and Mercury to compete. The challenge rages between moves of genius and tricks of low rank, with continual intervention from the outside on the part of the numerous protectors of the two contenders. At the end, Mercury is able to prevail and Vida describes in verse the ending of King and Lady against King, up to checkmate. Then the victorious Mercury seduces the nymph Scacchide, giving her the board and teaching her the rules of the game. From these deeds, according to Vida, the game of chess originated, deriving its name from the nymph." Cf. Marco Girolamo Vida, International Chess Festival:

http://www.cremonascacchi.it/festivalvida/index.php?page=pagina_mgvida

17 - For the translation of the Latin verse we used the version of the Scaccheide edited by Filergo. La scaccheide, poemetto; trasportato dal testo latino in versi italiani da Filergo (Scaccheide, a poem, translated from the Latin text into Italian verses by Filergo) Italy, 1810). Although it is a poetic transposition and not a simple Italian version, with a terminology sometimes different from the original version, the meaning of the Latin text is fully maintained.

18 - See the article My Heart has become a Taroch. Rocchi are here associated to the lover's sturdy thoughts and strength of feeling, the lover compared to a big fortress or stronghold, which the beloved, however, is presented as wanting to break down, to remove all hope of victory from the man. The topos of the chess game is also in an interesting Sicilian version of a clash between God and Lucifer entitled Luciferu jucava una mattina (One morning Lucifer was playing), Marucelliana Library, Ms. C 204, c. 89v.

19 - In Carlo Cozio, Il Giuoco degli Scacchi osia Nuova idea d’attacchi, difese e partiti del Giuoco degli Scacchi (The Game of Chess, New ideas for attacking, defending and ending Chess Games), Turin, 1766: we find “Avvertimenti al Bianco: La pedina del Rocco del Re, una Casa, l’Alfiere del Re alla casa 2, casa del suo Re, e poi s’arrochi, avrà giuoco forte” (Warnings for White: The King's Rook's pawn, one square, the King's Bishop to square 2, the square of its King, and then castle, will produce a powerful game), Book II, Chap. LVIII, page 297, and in Giambattista Lolli, Osservazioni Teorico-Pratiche sopra il Giuoco degli Scacchiossia il Giuoco degli Scacchi (Theoretical-Practical Observations on the Game of Chess), Bologna, 1763. "Della Difesa: Giuoco piano, dove l’Avversario nel tratto 4 s’arrocchi col Re, ecc" (On Defence: Gentle game, where the Opponent castles with the King, etc). Chap. IV, page 322.

20 - The objective that we set ourselves is a difficult task because it deals with finding a document of the period (end XV century - beginning XVI century), assuming that it exists and has not been destroyed, regarding an expression attributed to a card game by tavern patrons. All things considered it is unlikely that such an expression would have been deemed worthy of a written record. The case of chess is different. and we have many treatises because the game of chess, unlike cards, was considered very noble. Furthermore, the earliest known rules of the game of tarot date back only to the 17th century. Since in cases like this research could continue for years without achieving concrete results, what has been said here would remain only a hypothesis, albeit fascinating and quite plausible.

21 - In these expressions the word ti, unstressed form of the personal pronoun tu =you, acquires the form of the accusative case.

22 - The sonnet, attributed to Andrea Orcagna, a famous painter, sculptor and architect (1308-1368), is listed among the rhymes of Burchiello with number CXVII. Reference Edition: I Sonetti del Burchiello, ed. critica della vulgata quattrocentesca, a cura di Michelangelo Zaccarello, Commissione per i testi di lingua - Casa Carducci (The Sonnets of Burchiello, Critical Edition from the fifteenth century Vulgate, by Michelangelo Zaccarello, Commission for language texts - Casa Carducci), 2000, p.164.

23 - Tarot is mentioned as a tavern game by several authors. Among these, Alessandro Citolini of Serravalle in his Tipocosmia printed in Venice in 1561, writes: "Some others are tavern games; "la mora", "le piastrelle", "le chiavi", and then cards, common, tarot or fine, the suits of the common cards are coins, swords, cups and clubs, with 10. 9. 8. 7. 6. 5. 4. 3. 2. ace, king, queen, knight, page; the tarot card deck consists of the world, justice, the angel, the sun, the moon, the star, fire, the devil, death, the hanged man, the old man, the wheel, fortitude, love, the chariot, temperance, the pope, the emperor, the popess, the empress, the magician [gabbattèlla], the fool", pages 482-483.

24 - For nobles and intellectuals valued the famous phrase of Horace Odi profanum vulgo, et arceo (I hate the profane populace, and I keep it away from me), with which the first Ode of the third book begins.

25 - On the opinions of these authors see the article About the Etymology of Tarot.

26 - See the essays Taroch-1494, Taroch: vulgar Latin, Taroch: nulla latina ratione, About the Etymology of Tarot. In the latter case, together with our considerations, we have quoted the sentence of a macaronic text dated to the late XV century, highlighted by Ross Caldwell, where the term Tarochus, even if not related to the game, takes on the meaning of "idiot, fool". The former case, with the variant Taroch, is found in the composition Frotula de le dòne by Giovan Giorgio Alione, examined in our essay entitled Taroch-1494. On the possible derivation of the term from the myth of Bacchus, see the article Tharocus Bacchus Est.